Know your neighbour—Compton Dutta, FD Block

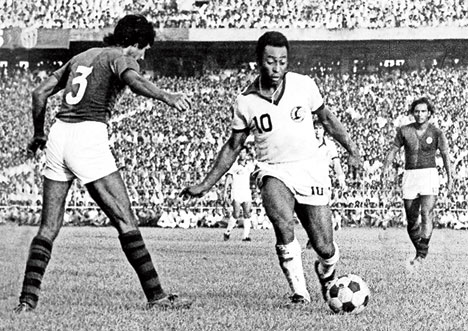

September 24, 1977. New York Cosmos was to face Mohun Bagan. But the ground at Eden Gardens was slippery after a shower. Pele was in two minds about taking the field. But the galleries were roaring his name in chorus. That warmed his heart. He decided to play. “And he played the entire match,” recalls Compton Dutta, who was a part of the Bagan XI.

Seated in the drawing room on the first floor of his FD Block house, Dutta proudly revisits the match. “They went ahead by a goal scored by Alberto, who was Brazil’s captain in the 1970 World Cup. Then (Mohd) Habib and Shyam (Thapa) scored for us and we were up 2-1. But the referee gave a penalty in the dying moments amid an uproar. We asked Pele if it was a penalty. When he nodded in negation, we requested him to tell so to the referee. In broken English, he said the referee was the supreme authority. Thus the match ended in a draw.”

But what he saw of Pele later left a lasting impression. “There was a party in the evening at Grand Hotel where many had gatecrashed. When Pele got on the dais Dhiren-da (Dey, the Mohun Bagan secretary) placed a silver crown on his head.” In a short speech, Pele said to be a good player one has to be good human being first. So unruly was the crowd that when he went to have dinner, he was being pushed around from all sides and sweating, yet never did the smile waver from his lips. That showed that he really walked the talk.” That is why, in Dutta’s eyes, Pele will always be greater than Maradona.

The Cosmos match motivated the Mariners so much that they won the triple crown that year — ILA Shield, Rovers Cup and Durand Cup. “Ours was a star-studded team then — with Prasun (Banerjee), Gautam Sarkar, Ulaganathan, Habib, Akbar, Shyam and (Subhas) Bhowmik.”

It was time for Mohun Bagan to turn around after a period of humiliation. The club had lost almost every time to arch-rivals East Bengal between 1970 and 1975. Dutta rose up the ranks at Southern Sports Association and then Kalighat Club, marking his entry in first division football. He also debuted for Bengal in Santosh Trophy in 1974. He joined Mohun Bagan in 1975.

“Dhiren-da and (Sailen) Manna-da reared me with parental care. Subrata (Bhattacharya) and Prasun had joined the year before. Ulganathan was also there.” But it was East Bengal that had all the reigning stars. In 1975, in the IFA Shield final, the red-and-gold brigade rubbed it in with a crushing 5-0 scoreline on Mohun Bagan’s own turf. “I was fielded in the second half of that match,” Dutta says.

The turnaround started the next year with a 1-0 victory over East Bengal in the league. By then, the club had managed to wean away P.K. Banerjee as coach and then, Bhowmik and Samaresh Chowdhury from the red-and-gold ranks. Club transfers in those days were the stuff of thrillers. Footballers were sometimes made to sign on the dotted line at gunpoint.

(Saradindu Chaudhury)

Transfer tales

Dutta recalls Shyam Thapa’s entry to Mohun Bagan. “Shyam was playing the nationals in Patna. The final was over and the team was staying at a guest house with East Bengal musclemen on guard outside the gate. Late at night, they fell in a stupor after a few drinks. Mohun Bagan recruiters flashed burning match sticks at a distance in the dark as signal to Shyam. He collected his kit and climbed down through the window of the bathroom. A car was waiting for him and he was whisked away to Dehradun and then Delhi. News spread like wildfire that Shyam had escaped. But when his flight was landing at Dum Dum, Manna-da was ready on the tarmac with a police contingent. So there was no way East Bengal could snatch him back.”

A loyal Mariner all his life, Dutta faced the strong arm of the club only once. “Hemen Mondol and Omar worked for Mohun Bagan and Mohammedan Sporting respectively while Jiban and Paltu were the musclemen for East Bengal.” Once he came home to hear a fair and well-built man wanted to see him. “I realised who he was when he gave his name. He said word was doing the rounds that Bidesh (Bose) and I were considering a shift to East Bengal and Dhirenda wanted to meet us. Despite protests, he made us get into his car and reach the tent. Dhirenda was surprised to see us and told him not to worry about our loyalty.”

Football passion in those days ran high. Waiting in queue for a ticket overnight was common. “I have known people to sleep in the open for two nights also,” he says. “When we won, there were celebrations in Mohun Bagan localities. Sweets would be distributed, flags would be hung and songs would be played on the loudspeaker.” But if the team lost crunch matches or even drew against small teams, there would be hell to pay. “Irate supporters badmouthed us and torched vehicles on Red Road.”

Dutta had the misfortune of staying in an East Bengal para — Jadavpur. “Sometimes I would be called names as I would pass by on my bike. I always stopped and protested. Once I returned home after a derby win to find the ambience tense. A local boy had come up to our second floor place and abused my mother. Ignoring her plea, I stormed out to see who it was. The boy was not home but I told his mother that his behaviour was unacceptable and I wanted to meet him. Of course, he never came but others dragged him to our house to seek an apology. Years later, the same boy would be among neighbours coming to me for tickets.”

Tragedy strikes

He became Mohun Bagan captain in 1980. The same year on July 16, Indian football witnessed a black day with 16 spectators dying during a derby at Eden Gardens. “The common belief is the violence was sparked by the on-field altercation between Bidesh and Dilip Palit.”

But Dutta offers a different account. “The violence erupted before the match started. We saw people being carried out by the police as we walked out of the dressing room. We did not realise they were dead.” He blames the thoughtless distribution of tickets that allowed supporters of both teams to sit together. “And when police appeared at the top of the tier to lathicharge the crowd in D1 — the only block in the stadium then to have an upper tier — spectators tried to jump down 20 feet to the lower tier or were already crushed in the stampede.”

His senior international career took off with the 1978 trip to Bangkok for Asian Games. He would go on to play two Nehru Gold Cups, two Merdeka Tournaments, President’s Cup, King’s Cup and pre-Olympics. But it is the 1982 Asiad in Delhi that is at the top of his mind. “A preparatory camp was held for two years at the site where Salt Lake stadium was being built. We were put up in under-construction flats in Karunamoyee,” recalls the right-back who would move into Salt Lake much later, in 1995.

But the sore point was the payment on national duty — a paltry Rs 2000 per month for two years — in place of the club pay cheques ranging from Rs 70,000 to a lakh a year. Sensing the discontent, an option was given and 21 players opted out. “Ours was a valid point. But the media portrayed us as traitors to the country. We started getting heckled everywhere. Finally Priyada (Priyaranjan Dasmunshi) called a meeting and mediated a truce. The AIFF agreed to take back six players, including me.”

Fighting with fever

During the trials, Dutta was down with malaria yet he was kept in the team. “We drew against China and won against Malaysia and Bangladesh. After every match, I would need saline injection at the medical unit. In the quarter-final, Pradip-da (P.K. Banerjee, coach) asked if I was up for it. I said yes. He promised to substitute me whenever I would raise my hand as signal of exhaustion. I fell frothing at the mouth after half time but there was no substitution despite my repeated signals. After I was finally taken off, I was just changing into a track suit when Sudeep Chatterjee, my substitute, blundered at the top of the box resulting in a last minute goal. Pradipda was weeping bitterly.” Only then did he realise that there were just two minutes left. “Had I known, I would have carried on.”

He did get to play at Salt Lake Stadium at the fag end of his career. “It was such an improvement from the sticky mud of the Eden surface which stuck to our studs in the monsoon.”

Another count on which he considers the present generation lucky is the live telecast of matches. Communication was nil when they went abroad. “Once on Puja-eve, we were returning from a match in Pyongyang, North Korea via Moscow. We had to take a roundabout route as India were denied access to China airspace in those days. But word spread that our flight had crashed. It was only after we reached that we found the reason for the grim atmosphere at the local Puja pandals.”

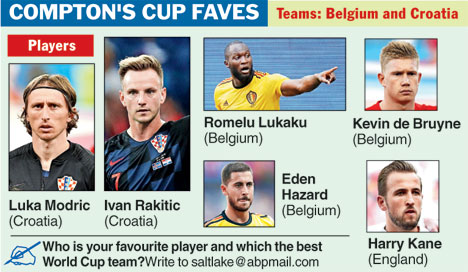

Watching the Asian teams assert themselves at the on-going Fifa World Cup, he laments the decline of India’s standard. “We don’t even play the top teams in the continent now. The Indian Super League (ISL) may be a well-marketed event but will it help Indian football?” he wonders.

source: http://www.telegraphindia.com / The Telegraph,Calcutta,India / Home> Calcutta / by Sudeshna Banerjee / June 29th, 2018

Dhirenda was surprised to see us and told him not to worry about our loyalty.