– Two bright young minds with shared roots in La Martiniere for Girls, Calcutta, are lighting up an Ivy League campus with their brilliance.

Jhinuk Mazumdar spoke to Vedika Khemani, Junior Fellow designate at Harvard University, and Tarang Kumar, Teaching Fellow at Harvard College, to chart their inspiring journeys

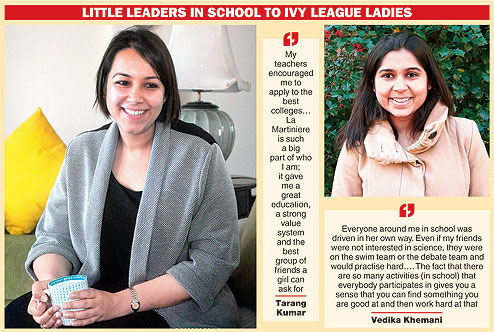

VEDIKA KHEMANI

As a toddler, she was fascinated by science museums. As a student of Class IV, she had already made up her mind to specialise in either physics or mathematics. As a teenager, she would hunt for answers to her inquisitiveness in the pages of books by Richard Feynman and Stephen Hawking.

Vedika Khemani, “science geek” from the Class of 2006 at La Martiniere for Girls, will now get to dine and discuss physics with Nobel laureates.

The 27-year-old has been designated Junior Fellow at Harvard University with effect from August, a position she earned by clearing an interview by a panel of distinguished academicians that included Nobel laureate Amartya Sen. She is the 94th and only the ninth woman physicist to be admitted to this elite group. No other Indian woman physicist has gone where she has.

The Harvard Society of Fellows, founded in 1933, is the most prestigious postdoctoral research fellowship in the US. Only 12 fellowships are awarded each year across fields ranging from physics to literature to law. The list of Junior Fellows in physics since the inception of the society includes top scientists and Nobel laureates like David Gross, John Bardeen and Kenneth Wilson.

Vedika’s extraordinary journey started at La Martiniere, where the school topper would help her friends with their math problems the day before an exam. After completing her ISC in 2006, she went to Harvey Mudd College and is currently finishing her PhD in theoretical condensed matter physics at Princeton University.

So, how did a girl of barely 10 decide in Class IV that she would study physics or math? “Those were the subjects I really enjoyed, and everything else I kind of did because I had to,” she told Metro.

Vedika describes her favourite subjects the way a poet would give voice to feelings. To her, math is “beautiful, pristine, neatly tied with a bow” while physics is “messy, chaotic, but then you discover patterns in that mess”.

She also finds it fascinating that “this really complicated system of so many trillions of electrons actually follows this one very simple and beautiful equation”.

A teacher in school remembers Vedika as “effortlessly brilliant, with an amazing memory”. But the able – and humble – student feels there is no alternative to hard work, discipline and drive.

“Everyone around me in school was driven in her own way. Even if my friends were not interested in science, they were on the swim team or the debate team and would practise hard…. The fact that there are so many activities (in school) that everybody participates in gives you a sense that you can find something you are good at and then work hard at that,” she said.

Her history teacher Behula Chowdhury, who Vedika remembers fondly, said the most striking thing about the precocious girl in class was the ease with which she could assimilate knowledge. “She was not one of those students who would jot down every note in class. Everything was inside her head,” recalled Chowdhury.

Vedika owes her love of physics and math to her father Navneet and maternal uncle Rajesh Kanoria, who she remembers would “willingly spend hours discussing esoteric math and physics problems that were well outside my course of study at school”.

Even when he returned home late from work, Navneet would not turn away from discussing any math problem his daughter came up with. “A message for all dads everywhere to invest time in their children instead of just paying the bills!” quipped Vedika.

To her mother Rashmi, Vedika gives credit for giving her “the courage to dream without thinking about any misgivings or limitations”.

Vedika had received fellowships from Berkeley, Stanford and Caltech, and a position from Microsoft, but she chose Harvard over everything else.

Last December, when she was to be interviewed at Harvard for the position of Junior Fellow, Vedika was struck by nerves just like any other young person on the cusp of a great career opportunity. The nervousness, which she says helps her prepare for such big occasions, disappeared the moment she stepped into the room filled with brilliant minds.

For half an hour, Vedika took questions and presented her work on “Many-body localisation” with the confidence of someone who knew her subject. “I had spent a lot of time on this project and the fact that all these people were interested in it and asking questions was really exciting,” she recalled.

But for all her achievements, Vedika compares her entry into Harvard as “that of one electron among those trillions” and refuses to dwell on it. “This position is only based on my potential to do something. In the grand scheme of things, what have I really discovered about physics yet? There is the prestige of a position, but that is nothing compared to actually figuring something out,” she said.

Vedika is still the same Wood Street girl who loves to have chaat near Vardaan market, Chinese at Flavours of China and rolls on Park Street. Whenever she is in town, which is at least once a year, she visits College Street to buy textbooks on physics and misses the stores that once dotted Free School Street.

And to all those who aspire to be the next Vedika, she is never far away for some friendly advice. “I always try to write back to students who email me asking how and where to apply,” smiled the 27-year-old.

TARANG KUMAR

Tarang Kumar, 31, had cited her experience of taking two classes in her alma mater, La Martiniere for Girls, in her application for the post of Teaching Fellow at Harvard College. “You have never learnt something until you are made to teach it,” she wrote in the application.

Tarang, who passed out of La Martiniere in 2003, is doing her MBA at Harvard Business School and the opportunity to be a Teaching Fellow is something she hadn’t planned for. The last time she had taught was 12 years ago – she was then a student of economics at Delhi’s St. Stephen’s College – and Tarang was drawn to the information session primarily because it was to be addressed by Gregory Mankiw, whose books she had read in college and wanted to “put a face to the name”.

“He was on the campus and it was super convenient,” she said of the session, attended by 600-odd students.

The experience encouraged Tarang to take “a shot” at becoming a Teaching Fellow and she was soon on board as part of “an army of 25-30” selected to teach economic theory to undergraduates. But Tarang refuses to make a big deal out of it even though “there are many who apply for the job but don’t get it”.

“The undergraduate college has developed a system where they recruit teachers from Harvard Kennedy School, Harvard Law School, Harvard Business School, PhD students and also full-time teachers,” she explained.

Although Tarang didn’t have any long-term career goal when she was in school, she always knew that she would study economics. “And my teachers encouraged me to apply to the best colleges…La Martiniere is such a big part of who I am; it gave me a great education, a strong value system and the best group of friends a girl can ask for,” she recalled.

Whenever she makes a trip home, Tarang’s to-do list includes time with her school friends and trips to Kookie Jar and Tolly Club.

At La Martiniere, Tarang had been the president of the Drishti Club that organises cultural events. Being involved in these activities gave her the opportunity to learn about teamwork and leadership, skills essential to success in any workplace. “All the activities we had, whether it was sports, debate or elocution, gave us a lot of opportunities to step up and take leadership positions even at the school level,” she reminisced.

Sharmila Mazumdar, her economics teacher in school, said of Tarang: “There is not much growth in our profession and the maximum reward we get is when our students do well across the country and the world.”

According to Tarang, what makes La Martiniere different from a lot of other institutes is that “even if academics is not your strong suit, you still could find a place”.

At Harvard, Tarang teaches for three hours a week and “prepares for two hours for every class that I take”. Preparation is something she can’t do without because students “are smart and ambitious and some of the questions stump you”.

The hours that she puts in mean “giving up on other things such as great speaker events, opportunities to travel, socialise, take certain courses and sleep”. Two to three classes a week is a “huge time commitment” also because there are occasions when her students need her help to prepare for an exam in the middle of her own tests.

But Tarang won’t have it any other way. “This has given me an opportunity to relearn economics; to stand up in front of the class and teach. I have had the benefit of having some good teachers and to share the experience with someone is a great opportunity,” she signed off.

What message do you have for Vedika and Tarang? Tell ttmetro@abpmail.com

source: http://www.telegraphindia.com / The Telegraph,Calcutta,India / Front Page> Calcutta> Story / by Jhinuk Mazumdar / Monday – May 16th, 2016