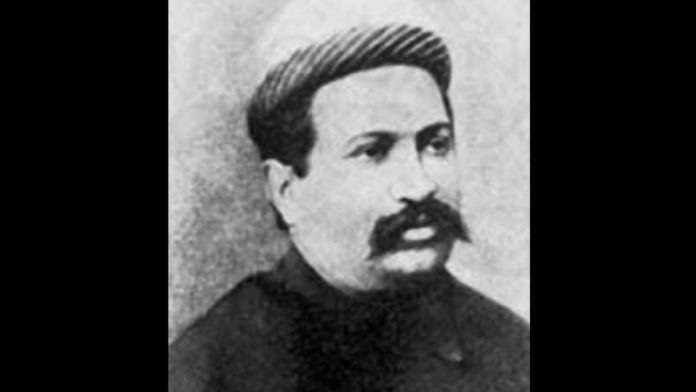

Epicentre of the renaissance and reform by day, the city was den of shocking behaviour by night, according to Hemendra Kumar Roy’s ‘Calcutta Nights’.

In these times of social distancing, Calcutta Nights , a recently translated crisp vintage work from 1923, beams up from the past the whole human mess of city life as we may fail to experience for a long time now – enticing , contagious with its mirth, sorrow and decadence, yet ultimately safe. Calcutta-ness is both a cult and a code.

That Calcutta, totem pole of cult, is a distilled city, a Xanadu rich with local detail yet universal, contemporary yet not belonging to any particular period, a continuum of experience. No wonder then, that this wondrous city, simultaneous epicentre of renaissance, nationalism, reform movements and debauchery, should inspire city sketches, first made popular in the mid and late 19th century by the inimitable Hutum Pyachar Naksha. Decades later Hemendra Kumar Roy, prolific and popular author of detective fiction, adopted a nom de guerre to have a go at chronicling the scintillating night life of Calcutta in the 1920s.

If books were bordello windows, their sepia light beckoning, Calcutta Nights would be one such, quite literally. A salacious account of what the night unravels, the book takes you behind the scenes, reports on the microcosm of hedonism, the power plays, symbiotic relations, the intimacies of a prostitute with her regular customer, the paanwali bartering and trading with the police, the beggar, the opium-smoker. What sets this book apart is the flawed and reluctant author.

A warning, apparently

A prolific writer of detective fiction, primarily for children and young adults, Roy probably stumbled upon this diverse and rich material probably while researching for his more innocuous detective novels – armed with a stout stick, he says, and at great personal risk. Against his better judgment, he writes about city la nuit, worried and embarrassed about the task at hand, the adirasa or eroticism that he has failed to avoid while raising the curtains of hell.

In his introduction, he rushes to reassure his readers that none of them will find Calcutta Nights obscene. It is, rather, written with the noble intention of sounding a warning to “fathers of young girls and boys”. Our Meghnad Gupta, author in hiding, is no Samuel Pepys, the veritable diarist of 17th century London who wrote himself into his salacious scenes, boasting about his own ardour and peccadilloes.

The city Roy writes about is a city of men, consumed by men. In the author’s own words this book is “ written for an adult male audience,” a sweeping exclusion that predictably rankles this reviewer’s entitled, liberal, feminist bourgeoise self. Said outrage is difficult to cull at first. Then, as the book shines with its vivid portrayals, the puritan author becomes part of the setting and it is possible to turn the judging “gaze” right back at him, to see him in all his troubled light.

Here was an author writing about hedonism at a time when the wave of nationalism was peaking, his puritan acuity often criss-crossing with an awakening of socialism. His feelings about the women he writes about swing from condescension and humble misogyny (empathetic and damning at the same time – a tone often taken when writing about giants by the best of Bengali literary stars, Sarat Chandra Chatterjee included) to genuine insight.

Atmospheric ride

A pacy read, the depiction is vivid and colourful. Despite his protestations the author is clearly an insider – therein lies the strength and authenticity of this sketch. The description is atmospheric. Roy bring alive, with cinematic realism, the night in which “owls flutter away…and gradually the swarthy ugly faces begin to peep and snoop.”

And slowly Chitpur Road transforms itself – weary clerks disappear, the streets are filled with the scented babus, their faces aglow with Hazeline snow seeking verandthe a belles. Kapure babus, hothat-babus, ingo- bingos, the rich, the white, the Marwari, Chinese, European women of loose morals, courtesans of Chitpur, lustful ladies of Kalighat, the poor prostitute, the wanton widow – each scene, as the chapters are aptly called, presents to us a glossary of social categories.

One of the most striking sketches is that of the Bhikiripara or beggar’s quarters. There are fabulously sensational bits, revealing the author’s – Roy had translated Bam Stoker’s Dracula – penchant for the supernatural and the fantastic. Particularly recommended are scenes from the Nimtala Crematorium and the one featuring a prostitute who beckons men into her room where a dead man lies, his throat slit open.

Translator Rajat Chaudhuri craftily balances archaic words with new ones, never upsetting the tonal authenticity of a period piece. Ultimately he strikes the right cadence – the voice often changing as it travels from Chitpur bordellos to the jazzy evenings in the Anglo quarters or the dim Chinese taverns.

For its depiction of the crowded and dense interplay of lives in the Calcutta of those days, this book is a perfect curl-up for these epic-dammed solitary afternoons. A treasure trove for every city addict has been discovered.

Calcutta Nights, Hemendra Kumar Roy, translated from the Bengali by Rajat Chaudhuri, Niyogi Books

source: http://www.scroll.in / Scroll.in / Home> Book Review / by Lopa Ghosh / March 29th, 2020