The Brahmo Samaj was founded on 20 August, 1828 in Kolkata by Rammohan Roy and Debendranath Tagore

The Sadharan Brahmo Samaj was denied the status of a minority religion in an order issued by the West Bengal Minority Affairs and Madrasah Education Department in September 2017. The context was that of the Samaj constituting the governing bodies of eight prominent colleges in Calcutta. The order proclaimed that as the Samaj was not a “separate minority religion”, the colleges governed by it should be treated as “non-minority Government-aided Colleges.” It further stated that the governing bodies of these institutions, run by the Brahmo Samaj Education society, be dissolved. The Samaj decided to take the West Bengal government to court, stating the government was in an utter state of “confusion”. It is rather ironic that an institution, time and again divided over its vision and constitution, arraign others for getting bewildered by its habitus.

But we will refrain from rallying on those walkways, and instead look back at the checkered yet fascinating history of this once reformist movement, founded on this very day in 1828 by Ram Mohan Roy, Tarachand Chakravarti, and Dwarkanath Tagore among others.

Emerging from the gatherings of educated, upper-caste elite bhadraloks and their newfound belief in religious reform and congregational praying, the Brahmo Samaj in its earliest avatar organised weekly services with marked segregation. The recital of vedas were performed by orthodox priests, only for the Brahmin members of the congregation. It was followed by commentaries on the Upanishads and the singing of songs and hymns which were open to all. This did not fit very well with the greater idea of universal worship that lay at the core of the Samaj. After Ram Mohan’s departure for England in 1830, and his subsequent death in 1833, it was Debendranath, Dwarkanath’s son, who took charge of the Samaj. Debendranath established the Tattwabodhini Sabha, which became the hub of the cultural elite in Kolkata, gathering some 800 members at one point of time.

The era of the Tattwabodhini Sabha (1839-1859) thus ushered in a significant and creative epoch in the history of the Brahmo Samaj which had for once come to receive the sincere co-operation of nearly all the progressive sections of the contemporary Hindu society. The unification of these diverse elements of national life on a common platform was certainly an organisational achievement which reflects credit on the tact, foresight and earnestness of the young Debendranath.

Rituals and Adi Brahmo Samaj ceremonials of the new church were formulated, the most prominent among these being the system of initiation. It started with the initiation of Debendranath and his friends in 1843. The initiated Brahmo was a new phenomenon in the history of the faith. Along with initiation came the special status of membership system and compulsory subscription for the initiated was introduced. A notable doctrinal change that took place was the abandonment of the belief in the infallibility of the Vedas. It was decided and formally declared that the basis of Brahmoism would henceforth be no longer any infallible book, but “the human heart illumined by spiritual knowledge born of self-realisation”.

The Brahmo movement spread rapidly in the country and by 1872 the church had succeeded in establishing altogether one hundred and one branches throughout India and Burma. In one respect however a notable change had taken place in the nature of Brahmoism from this epoch. The Samaj had now definitely taken the shape of a religious sect or community with its own creed, rituals and regulations. This began increasingly to mark it out as a separate religious unit, distinct from other existing sects.

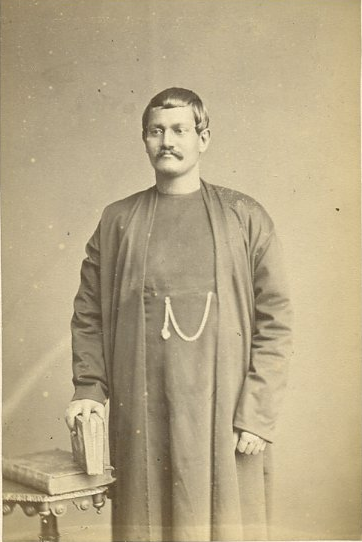

The next phase of the Brahmo movement is dominated by the dynamic personality of Keshub Chandra Sen (1838-84) who joined the Samaj in 1857. Debendranath loved the young man and appointed him an acharya of the Samaj. Keshub was the first non-Brahmin to be given that position. In 1864 he undertook an extensive tour of the presidencies of Madras and Bombay and prepared ground for the spread of the Samaj in Southern and Western India. But serious differences regarding creed, rituals and the attitude of the Brahmos to social problems had arisen between Debendranath and Keshub, men of radically different temperaments and the Samaj soon split up into two groups – the old conservatives rallying round the cautious Debendranath and the young reformists led by the dynamic Keshub. The division came to the surface towards the close of 1866 with the emergence of two rival bodies, the Calcutta or Adi Brahmo Samaj, consisting of the old adherents of the faith and the new order (inspired and led by Keshub) known as the Brahmo Samaj of India.

In spite of the dynamic progress of the Brahmo movement under Keshub, the Samaj had to go through a second schism in May, 1878 when a band of Keshub Chandra Sen’s followers left him to start the Sadharan Brahmo Samaj, mainly because their demand for the introduction of a democratic constitution in the church was not conceded. The body led by the veteran Derozian Shib Chandra Dev comprised some of the most brilliant and talented young men of the time including Sivnath Shastri, Ananda Mohan Bose, Dwarkanath Ganguli, Nagendranath Chatterjee, Ram Kumar Vidyaratna, Vijay Krishna Goswami and others. They were all staunch democrats and promptly framed a full-fledged democratic constitution based on universal adult franchise, for the new organisation. It was declared in Bengali mouthpiece of the Samaj Tattwakaumudi that the Brahmo Samaj was about to establish a ‘world wide republic’ by replacing inequality with equality and the power of the king with the ‘power of the people’. The new body displayed, considerable vitality and dynamism in making inroads into fresh fields of philanthropy and politics. Quite a few of its leading figures took part in the activities of the Indian League (1878), the Indian Association (1878) and the nascent Indian National Congress. It has proved up till now, as demonstrated at the outset, a powerful and active branch of the Brahmo Samaj in the country.

source: http://www.telegraphindia.com / The Telegraph, online edition / Home> Culture / by Abhirup Dam / August 21st, 2019