Monthly Archives: June 2019

10

09

Birds of Bengal at Sweden auction

The paintings by Zayn al-Din were commissioned by Mary Impey, an English natural historian and patron of the arts in Bengal

Two watercolour and pencil-on-paper artworks painted in Calcutta in the late 18th century by one of the most famous exponents of the Company School of Art will go under the hammer at the world’s oldest auction house in Sweden on June 12.

The paintings by Zayn al-Din were commissioned by Mary Impey (March 2, 1749 -February 20, 1818), an English natural historian and patron of the arts in Bengal. She was the wife of Elijah Impey, the first chief justice of the Supreme Court at Calcutta (1774-82), who had infamously sent Maharaja Nandakumar — a highly-placed officer in the nawabi administration — to the gallows on charges of perjury.

Falsa Tree with King’s Nightingale, dated 1782, and Parrot in a Parkar Tree, dated 1779, have been in the possession of a Swedish family for long.

“We are immensely proud to present these rare artworks. We are not sure how they reached Sweden. They have been in the same Swedish family for a long time and this is the first time that they reach the market,” Victoria Svederberg Bojsen, a specialist in classic and modern art at the Stockholms Auktionsverk (Stockholm Auction House), founded in 1674, told Metro over phone from Stockholm.

“The estimate price is Euro 51,000 (Rs 40 lakh) to 61,500 (Rs 48 lakh). However, we believe they will reach an even higher price. Our hope is naturally that they will now be returned to India where they originated,” she said.

Birds are the subjects of both the paintings. Falsa Tree with King’s Nightingale is a 53.5cm x 75cm canvas.

The inscriptions on both pictures read: In the Collection of Lady Impey of Calcutta. Painted by Zayn al-Din Native of Patna 1782.

“Both paintings include a description of the subject in Persian — Darakht ban falsa, Shah Bulbul in the first and Madna Tota, Darkaht Pakar in the other. The artist’s name is also written in Persian,” said Nandini Chatterjee, associate professor of history at the University of Exeter in the UK.

Metro had sent the images to Chatterjee, who is part of a research on two sets of natural history drawings produced between the late 18th and early 19th centuries in Calcutta. The drawings are held at the Victoria Memorial Hall and the Royal Albert Memorial Museum & Art Gallery in Exeter.

The Impeys moved to India in 1773 after Elijah Impey was made the chief justice of Bengal. They set up a menagerie at their house in Calcutta’s Middleton Row. When they shifted to Fort William two years later, they started a collection of native birds and animals on the extensive gardens of the estate.

Mary Impey commissioned several local artists to paint the fauna and flora they had collected. Her three principal artists were Sheikh Zayn al-Din, and brothers Bhawani Das and Ram Das. All three had come from Patna.

Together, Zayn al-Din and the Das brothers painted more than 300 artworks, half of them of birds. The collection, often known as the Impey Album, is an important example of Company style painting.

“With the decline of the Mughal courts, the artists sought the patronage of Europeans. These artists had to change their traditional techniques to suit their new masters. These revisions included a more accurate representation of the subject and a change in perspectives,” said Jayanta Sengupta, the curator of the Victoria Memorial.

Little is known of Zayn al-Din, the artist whose works will be auctioned in Sweden next month. He is known for his extraordinarily detailed paintings for the Impey Album. His drawings of mountain rats, hanging bats, parrots and storks serve as interesting zoological studies and are now preserved at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford.

“The artworks from the Impey Album rarely reach the international market and the few that have been sold previously at Christies, Sothebys and Bonhams have fetched between $80,000 (Rs 55.5 lakh) and $140 000 (Rs 97.7 lakh),” Bojsen said.

The real study of the Indian subcontinent’s natural history is said to have started with the Mughals. Baburnama — the memoirs of the first Mughal ruler — has beautiful illustrations of birds and animals. Shah Jahan also took a keen interest in the flora and fauna.

With the fall of the Mughals, the artists sought the patronage of Europeans. Calcutta became a thriving centre of the (East India) Company school of painting.

“India was an unknown land for Europeans and along with its indigenous archaeology and history, they also wanted to explore its abundant flora and fauna. Imperial documentation differs from its Mughal predecessor in scale and systematic approach,” Sengupta said.

“Mary Impey was part of a circuit of Europeans who commissioned paintings of Indian natural history. Apart from the pictorial documentation of flora and fauna, the extensive notes kept by her about their habitat and behaviour were of great use to later biologists,” he said.

The collection went to England with the Impeys in 1783 and were sold at a London auction in 1810. Several pieces are in various museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.

“The style of inscription, and the handwriting is identical to other paintings all around the world. I do not believe Zayn al-Din’s name is in his own handwriting. It was probably written by a British collector, maybe Lady Impey herself. Many such British Orientalists (and perhaps some of their spouses) knew Persian,” Chatterjee said.

Some of Zayn al-Din’s works are at the Royal Albert Memorial Museum too. “But those have his name written in English and Bengali, perhaps by a collector who was interested more in the vernacular language, than Persian, which was the Mughal language of administration and courtly culture,” Chatterjee said.

source: http://www.telegraphindia.com / The Telegraph, online edition / Home> West Bengal / by Debraj Mitra in Calcutta / May 28th, 2019

The romantic story behind Odisha’s Belgadia Palace

A 200-year-old palace in Odisha has a Bengal connection — a little-known love story

For most tourists, Baripada is nothing more than a gateway to the Simlipal National Park, famous for its tigers and elephants, in Odisha. That there could be tucked deep within the small town an iridescent palace with an untold love story at its core, is not common knowledge.

Belgadia Palace is now home to the descendants of the erstwhile kings of Mayurbhanj, the Bhanj Deos. Praveen Chandra Bhanj Deo belongs to the 47th generation. He lives in a part of the palace with his wife, two daughters and his 91-year-old mother. On the initiative of his daughters, Mrinalika and Akshita, most of this 215-year-old palace is now open for pubic viewing. Says Akshita, “We want to make people aware of the legacy of our ancestors in the district as well as in the state of Odisha.”

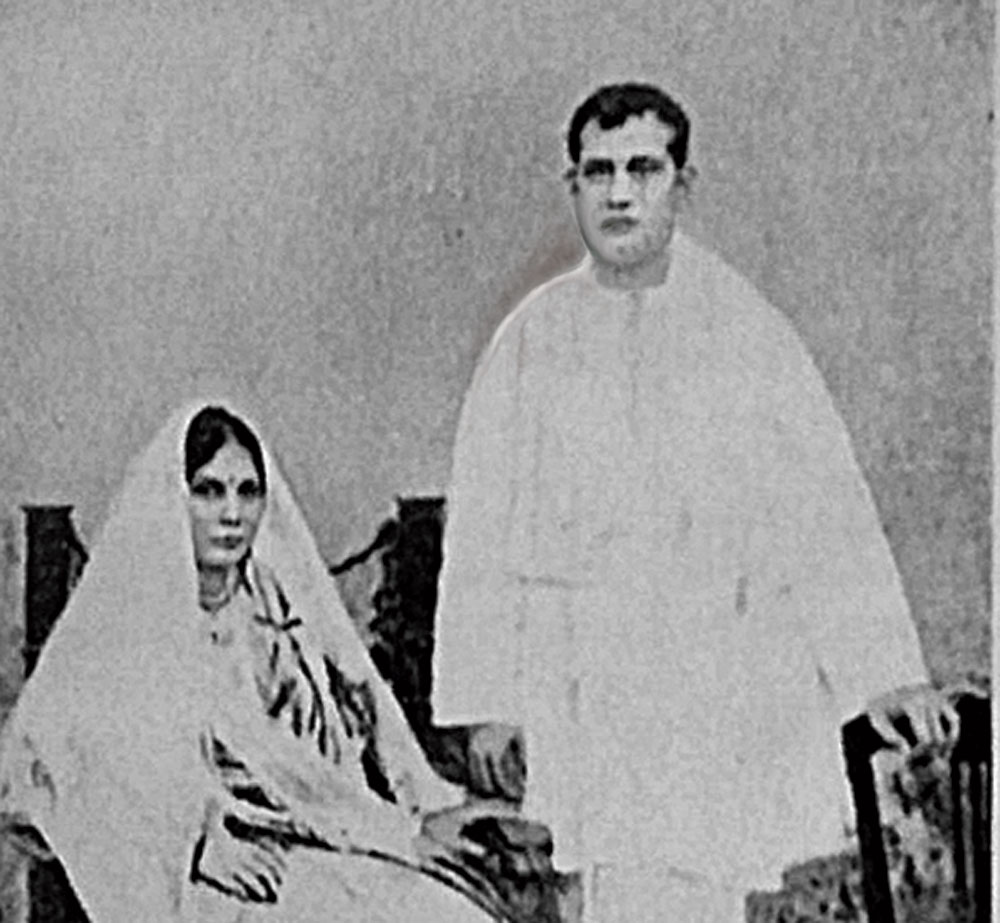

Before throwing open the palace doors, the sisters undertook a thorough recce of the place that revealed a gem too many. One such was the tumultuous love story of their ancestor Sriram Chandra Bhanj Deo and Sucharu Devi, the third daughter of Keshub Chandra Sen, philosopher and social reformer of 19th century Bengal.

Sriram Chandra met Sucharu Devi in Darjeeling. She was educated, enlightened and a 15-year-old girl who was not in purdah. He was 18 and looking for a wife who would be his companion. After a brief courtship they got engaged.

That was in 1889. But the crown prince’s family vehemently opposed the match. “The daughter of Keshub Chunder Sen as Maharani of Mayurbhanj! The daughter of that rebel, that revolutionary! To the conservative, orthodox powers in the Hindu state this was preposterous,” reads Sucharu Devi’s biography written by her daughter, Joyoti.

The young prince was no rebel; he toed the family line and married a girl from a local royal family. But the romance between him and Sucharu Devi did not die. “We tried to persuade her to marry but nothing would induce her to forget her lover,” writes Suniti Devi, her elder sister — the erstwhile queen of Coochbehar — in her autobiography.

Sriram Chandra’s first wife, Lakshmi Devi, gave birth to two sons and a daughter and thereafter, she died of smallpox. Writes Suniti Devi, “The Maharaja’s wife died, and he came back to ask my sister to marry him. The marriage (sic) took place in Calcutta, and for some time they led the happiest lives.” This was 1904.

Since the Maharaja never dared to take Sucharu Devi to his native state, he built for her the Rajabagh Palace in Calcutta’s Mayurbhanj Road — now the building houses the J.C. Ghosh Polytechnic. They had two children — Dhrubo Narayan and Joyoti. Sriram Chandra met with an untimely and mysterious end in 1912. The accepted version is that he was accidentally shot while he was out on shikar.

Even though the construction of the palace began in 1804, it was developed in several phases. The present interiors were especially designed for Sucharu Devi since she was not welcome in the main Mayurbhanj Palace. But she visited Mayurbhanj and her palace for the first time only after her husband’s death, on invitation of her stepson, Purnachandra Bhanj Deo.

She continued to visit Mayurbhanj occasionally and was associated with social work and spiritual work in Baripada. Her involvement with the Nababidhan Brahma-Mandir in the centre of the town is known. A torch-bearer of feminism in India, she was elected president of Bengal Women’s Education League in 1931.

Sucharu Devi died in 1961 in Calcutta. To date, the rooms and verandahs of Belgadia Palace, we are told, are imbued with her refined sensibilities. As she was an accomplished painter it is believed that artists like Jamini Roy and Hemendra Nath Majumder had visited the palace.The furniture, furnishings, paintings and photographs in the palace continue to reflect her touches. Says Akshita, “She had a deep influence on most of the activities of the Maharaja, who was known as the philosopher king and also revered for his public welfare efforts.” And that is what makes intriguing the fact that to date, there is no portrait of the woman herself on display at Belgadia Palace. “This happened probably because she was never accepted wholeheartedly by the larger family and state subjects because of the difference in caste, creed and religion,” reasons Akshita. She and Mrinalika have plans to find and display the love letters and photographs of Sriram Chandra and Sucharu Devi, for all to see and appreciate.

In a letter dated January 31, 1904, the 32- year-old Sriram Chandra writes to Sucharu Devi proposing marriage once again. It goes: “Dear S… Will you then share my sacrifices if I ask you to sacrifice all worldly pleasures and to be my spiritual companion? That seems to me at present to be the voice of the Almighty. Yours S.R.C. Bhanj Deo.”

source: http://www.telegraphindia.com / The Telegraph, online edition / Home> Heritage / by Prasun Chaudhuri / June 02nd, 2019