Monthly Archives: June 2016

12th

11th

10th

Halmari CTC tea pips own feat, breaks Rs 500 barrier

Kolkata:

Halmari, the first among Assam varieties to find a place at the Harrods Top Tier Tea Gift Box, may soon be called the Sergey Bubka of CTC tea. The former Ukrainian pole-vault icon broke his own world record 16 times. The CTC (crush, tear and curl) tea produced on the plush plains of this Upper Assam estate has already surpassed its own feat four times in just two years. Late on Tuesday, it created history by vaulting past the Rs 500/kg barrier.

Nine sacks of Broken Pekoe (BP) CTC tea belonging to Halmari Tea Estate fetched a price of Rs 501/kg at an auction brokered by J Thomas & Co. The buyer was Prasad Tea , a tea-buying house in Siliguri. Last July, another Broken Pekoe variety of Halmari estate had fetched a record price of Rs 441/kg. The buyer then was Kolkata’s Sealdah Tea House . Only eight days before that, Halmari, owned by Kolkata-based Amarawati Tea Company , had grabbed eyeballs when another batch of its Broken Pekoe went for Rs 426 a kg.

“Of the nine or 10 CTC varieties that have gone for over Rs 400 a kg so far, seven are from Halmari,” owner Amit Daga told TOI.

Dissecting the character of the record-breaking tea, Krishan Katiyal, CMD of city-based J Thomas & Co, the world’s largest tea auctioneer, said: “This tea is of surprisingly excellent quality for an early second flush variety. The liquor is smooth, full, sweet, malty and mellow.”

Katiyal added that he expects more such good quality tea from Halmari as “the garden’s quality is on an upward curve”.

Daga feels he is lucky to be the owner of one of the “best-placed gardens on earth”. Located 28km from Dibrugarh town, the 374-hectare estate boasts a rich loamy soil suited to produce high quality tea from pedigree clones.

“I also congratulate my whole team for the feat. The courage of the buyer is also commendable to say the least. Preparing such a clientele is not an easy job. It seems the Indian consumers are graduating to the next level for quality tea,” he said.

Stressing on the need to maintain quality, the Halmari owner said: “We are 100% EU-compliant as we export to European clients. But I have no idea why the brand is getting so much value for the past 20-25 years.”

Over 1,000 people work at the Halmari estate to produce around 9.5 lakh kg tea a year.

Bharat Arya , director & CEO of J V Gokal & Co, one of the largest exporters of tea in India, lauded the efforts put in by Halmari, saying the owner must be treating his tea leaves like his baby. “They handle it very well. Thus the tea forms a nice thick cup. It is brisk, strong with a gutty liquor. Basically the garden’s raw material is good.”

Speaking from Siliguri, Raju Prasad, owner of Prasad Tea, said the CTC tea that he bought was better than most Darjeeling varieties although one should not compare between the two. “I paid a good price for an excellent batch of tea. This particular tea is mild and bright bodied. It strikes the taste buds as and when one sips it,” he said.

Prasad has already found buyers for his latest batch. “It will be divided into two parts. One will travel to a Maharashtra seller. The other lot will be sold in the Siliguri market. It is all set to fetch Rs 650-700 a kg in the market,” he said

If you think this is not a big price to pay, think again. Unlike Darjeeling, which goes for thousands per kg and has a select clientele, the CTC caters to the mass market and India is the world’s largest consumer in the category, running through 1,080 million kg of CTC tea in 2015-16. Of the country’s total tea production of around 1,200 million kg last year, CTC accounts for almost 90%.

Asked whether Indian consumers are prepared to pay good price for quality tea, Prasad said, “Today’s tea aficionados are confident about quality. So, they don’t mind paying for it.”

source: http://www.timesofindia.indiatimes.com / The Times of India / News Home> City> Kolkota / by Sovon Manna / June 09th, 2016

08th

07th

06th

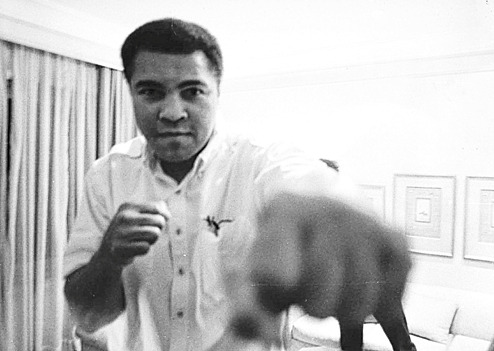

When my right fist was on Ali’s jaw – CLOSE ENCOUNTER WITH TRULY THE GREATEST

I chased 100m drug cheat Ben Johnson from the 1988 Seoul Olympics and caught him… for an interview at his home in Toronto. I bit my nails during the football World Cup final in Rome in 1990 when Germany’s Andreas Brehme scored against Maradona’s Argentina in a penalty shootout to win the trophy. I joined Carnivale-style Brazilian fans in downtown Los Angeles after they won the World Cup of football in 1994. I was with Sunil Gavaskar when he presented Kapil Dev with a bottle of champagne at the WACA in Perth in 1992 after the Indian all-round legend got his 300th wicket. I saw Kapil dance on the bed of his Ahmedabad hotel room after becoming the highest wicket taker in the world in 1994. I had goosebumps when the Indian national anthem played to announce P.T. Usha as the sprint queen of Asia in South Korea in 1986. I’ve seen Boris Becker ‘boom boom’ his way to a Wimbledon title.

You could say that I’ve been there and done numerous international sporting events as a sports journalist in the 1980s and 1990s. But whenever I am asked about the highlight of my life, my answer is always the same: my encounter with Muhammad Ali at Taj Bengal, Calcutta, in 1990.

It went down like this. Word got around that The Greatest was visiting Calcutta for a community event, unrelated to sport. We at Sportsworld magazine (from the ABP Group of publications) were desperate to get an interview, and needed to identify the organisers of the community event. Having done so, we sought to find a ‘connection’ to the organisers. The link was a man named Dada Osman, a leading figure in Calcutta’s rugby scene and an old family friend of my parents.

Osman organised for me to meet Ali in his hotel room for 15 minutes! The arrangements included permission for us to take a photographer and one other person. This made for plenty of problems because everyone I knew wanted to be my chaperone. You would expect enthusiasm from a bunch of young journalist colleagues. But the demand to accompany me to meet Ali went far beyond my colleagues and friends. My father, Neil O’Brien, known to be an avid boxing fan, put in a request as well. How could I turn him down, when it was part of folklore that the quiz legend Neil O’Brien could rattle off every world heavyweight boxing champion in chronological order since the titles began!

So off we went, father, son and another legend, Calcutta’s best-know sports photographer, Nikhil Bhattacharya, to see the ultimate Legend. To set the scene, it must be pointed out that by this time Ali’s Parkinson’s was well publicised, and we were warned that it would not be a smooth-sailing question-and-answer session.

I knocked on the hotel room door a couple of times and after a little while, it opened. I stood there looking at this big white bath robe right in front of my face. My eyes travelled upwards, and there IT was: the Louisville Lip. From the photographs I had seen, Ali didn’t seem as big a man in comparison to some other boxers of his generation. But I was astounded to see this large frame standing in front of me. It was later that I realised it was not only his physical stature; it was also his awesome presence and aura which made him look bigger than he actually was. There is only one word which comes to mind every time I tell this story.

MAJESTIC! That’s what he was. And mind you this was way past his glory days. He still floated gently like the butterfly he claimed to be. The raving and ranting had been replaced by slow and soft speech. But there was no denying that there was something special about this man. He radiated greatness by his mere presence. I honestly don’t remember what questions I asked, but I recall he wasn’t able to provide long answers. Just a simple ‘yes’ or ‘no’. As an interview it wasn’t very informative.

All I remember is that he sat back on the large sofa, white bathrobe wrapped around as if he had just come out of the boxing ring. I sat at the other end of the sofa… on the edge of it really. My dad sat on the single sofa at the side. Nikhil da went about his business, click, click, click.

There are two other things which are etched in my memory. At the end of our 15 minutes, my dad, unannounced to me, pulled out an enlarged black-and-white print of a photograph of Ali in the famous pose after he had knocked out Sonny Liston to win his first of three world titles. I recall feeling a bit embarrassed, because as a journalist I always refrained from asking sportspersons for autographs, and posing for photos with them. I remember thinking; I had never witnessed my father pay such reverence to any other person. Such was dad’s passion for this legend that he stooped to break my unwritten rule of no autograph/photograph.

Dad’s request gave me courage to ask my last question; and I couldn’t help but ask it. “Ali sir, may I take a photo with you?”

He stood up very slowly, I jumped to my feet. Nikhil da set himself up to take the shot. Just when Nikhilda said “ready?” something got into me. I raised my right fist and placed it on Ali’s jaw to pose for the photo. Perhaps at the back of my mind I was aware that his Parkinson’s would not allow him to ‘sting like a bee’ in reaction to this bold step of mine. I was right. He merely looked at me, leaned forward and the man, known for his classic one-liners, whispered in my ear, “BE COOL, FOOL!”

The champion, his body ravaged by something beyond his control, had not lost his wit, his class and his dignity.

Over many years, when I came across media reports that he was ill, I always told myself that one day I would write again about our meeting to relive the Legend of Ali to the current generation. Sadly, that day has arrived today, when my teenage son, born 20 years after Ali retired, burst into the room to announce, “Dad, sad news: Muhammad Ali has died.” My son knew it would be sad news for his dad, because he has heard on numerous occasions his dad tell the story of the encounter with Muhammad Ali. The time had come for me to write the story, as a eulogy and tribute to the great man. I’m glad I passed on the Ali legacy to my children. I had to, because I have never been so in awe of a person ever in my life as I was with Muhammad Ali that day in the hotel room in Calcutta.

Truly the Greatest! RIP.

Andy O’Brien, always a sports fan and always a Calcuttan, worked for 13 years with Sportsworld magazine. He migrated to Australia in 1996.

source: http://www.telegraphindia.com / The Telegraph,Calcutta,India / Front Page> Caclutta> Story / by Andy O’Brien / Sunday – June 05th, 2016

A window on history – Remains of Portuguese days

Memory can be extraordinarily flexible. As the Portuguese coast recedes and our ship edges into Spanish waters, Évora’s reticence about the communist upsurge in the surrounding region called Alentejo reminds me of the stonewall I encountered in Hyderabad trying to talk of the Telangana revolt. Most people assumed I meant the agitation for a separate state. Few even remembered the earlier armed rising linked to the 1948 Calcutta Conference which also resulted in Malaya’s prolonged and bloody Emergency.

“In the Alentejo, you travel naturally with and to History,” writes a local chronicler. It didn’t know a revolution that never was like West Bengal where revolution means speeches, and revolutionaries fatten in office for decade after decade. Alentejo’s was a revolution that failed like Telangana’s. But without the violence. It also suffered from a confusion of aims. Both mixed the local with the global. The immediate impetus in Telangana was opposition to the Nizam of Hyderabad’s regime. However, the Calcutta Conference spoke of a wider ideological purpose. In fact, many believe the insurrection petered out because Moscow’s rapprochement with New Delhi prompted the Comintern to abandon the conference’s ostensible hosts, the World Federation of Democratic Youth and the International Union of Students.

The peasantry around Évora where we spent several delightful days also felt betrayed. Évora is a charming medieval walled town whose university students in black medallion-studded cloaks over their frock coats sing and dance in the cobbled central square, the Praça do Giraldo, chasing away horrible memories of the burnings that took place there during the Inquisition. Founded in 1559, the university closed down in 1759, when the authoritarian prime minister of the day turned out the Jesuits. It didn’t reopen until 1973. Évora was under Muslim rule for 400 years. They came to help a local contender for power and stayed to consolidate their own rule.

The real contradiction was between radical young officers of the Movimento das Forças Armadas and peasant and student protesters clamouring for reform in 1974. The officers overthrew Portugal’s long dictatorship in a last-ditch attempt to pre-empt more drastic change. The protesters in the streets who gave them carnations which they put into the barrels of their guns – hence the name Carnation Revolution – hoped for a drastic social and political transformation. The organizations of workers and young people that sprouted all over the Alentejo resembled the proletarian councils (soviets) associated with Russia’s October Revolution.

Ordinary soldiers weary of war also set up their own committees to demand democratic rights and an end to Lisbon’s imperialist wars. If national liberation movements could rock the foundations of colonial rule in the so-called “overseas provinces” of Angola, Cape Verde, Guinea-Bissau, Mozambique, and São Tomé, they asked, why should the metropole remain under the corporatist yoke? Landless labourers who toiled on the great estates called latifundio seized the fields they farmed. According to government estimates, about 2,200,000 acres were occupied. Some 1,000 estates were collectivized.

Something like the Spanish Civil War seems to have been fought out in miniature but with roles reversed. Claiming that fascism had to be defeated, Portugal’s reformist Socialist Party and Stalinist Communist Party sprang to support the MFA and the junta it had installed. Social historians believe they destroyed the chance of a socialist revolution. Lisbon promulgated the Land Reform Review Law in 1977. The collectives were dissolved. The original owners repossessed the latifundio. Portugal’s aristocracy has retained its wealth through centuries of upheavals. Some of the mansions and manor houses have been in the same family for generations. Hoardings in the vineyards along the road from Évora to Lisbon proudly proclaim the ownership of families like the Fonsecas. No lingering memory of the 1974 uprising disturbs Évora’s tranquillity.

The official justification is that the Alentejo collective farms could not be modernized. In the mid-1980s, agricultural productivity was half that of the levels in Greece and Spain and a quarter of the European average. Land holdings were polarized between small and fragmented family farms in the north and inefficiently large collectives in the south. Even Bangladeshi immigrants who had managed to acquire Portuguese work permits fled to more prosperous economies. Decollectivization was said to be the only hope.

I learnt more about Évora and its unexpected links with Bengal from Trilokesh Mukherjee, my graphic artist friend who lived in the Dordogne in France for many years. Now he seems to spend more time in Oxford and South Wales but remains a storehouse of the minutiae of Indo-European culture. Trilokesh told me Évora was the birthplace of Manuel da Assumpção, an Augustinian monk who spent many years near Dhaka and is credited with writing and printing the first dictionary and grammar of the Bengali language, Vocabulario em idioma bengalla e portugueza. “The Portuguese even cast some Tamil and Malayalam types. But they never could cast Bengali types.” It’s a matter of everlasting regret to Trilokesh that this final triumph eluded the Portuguese. “The first book to be printed in Bengali was printed in Lisbon though the writer, translator and the compiler came from Évora,” he wrote. Alas, it was set in Latin type.

Évora’s state library treasures another historic document, the manuscript of Brahman-Roman-Kyathalik-Samvada: an argument on Law between a Roman Catholic and a Brahmin by the Bengali Dom Antonio de Rozario. Dom Antonio’s life is shrouded in mystery. No one knows his Bengali name. He was apparently a princeling of Bhusana, which some place near Dhaka and others near Jessore. According to one version, Mug pirates took him to Arakan as their prisoner. Another has it he was sold into slavery in Goa. Both agree that another Portuguese Augustinian priest was his saviour and that he converted to Christianity.

The reinvented Dom Antonio is believed to have converted 30,000 Hindus in and around his estate, thereby arousing the wrath of the Jesuits in Goa who sent a senior priest to investigate. He confirmed Dom Antonio’s proselytizing success but added the converts had little knowledge of Christianity and had been paid to be baptized. It must be added before ghar wapsi fanatics reach for their purifying water that this was the competing camp’s verdict. No rivalry is more relentlessly bitter than that between the pious who are convinced of their monopoly of the truth.

Religion and language are the two main links. Vasco da Gama wasn’t quite the pirate in priest’s clothing that Bharatiya Janata Party loyalists made out on the 400th anniversary of his landing at Calicut, but he did have a strong religious motivation. Another Portuguese sailor, Luís de Camões, called Portugal’s Shakespeare, immortalized his achievement in the epic poem, The Lusiads. If Calcutta had Anthony Feringhee (Hensman Anthony), Dhaka’s Christians revere Sadhu Antoni (St Anthony of Padua). Some credit the Portuguese with creating Bengal’s first modern city in Hooghly. Others hold their imports of tobacco, potato and guava changed Bengali taste for all time.

With so many connections, it was exciting to stumble upon a Bengali gift to Portuguese (or so I imagined) when my wife was allotted the janela seat on the train to Sintra. I emailed a friend in Calcutta who passed it on to Aditi Roy Ghatak who messaged me from Macau, where she was holidaying, to say the former Portuguese colony had given her a janela on Portugal. I now learn that far from being Bengali, janla is an import like potato, guavas or tobacco. Derived from the vulgar Latin januella, the Portuguese janela travelled east with those first Europeans to inspire the Sinhalese janelaya and Tamil cannal. Our own janla is like almirah or kameez. Borrowing within reason is all right providing it doesn’t prompt Mamata Banerjee to follow the late P.N. Oak and claim that Big Ben and the Eiffel Tower are really Bengali creations.

source: http://www.telegraphindia.com / The Telegraph,Calcutta,India / Front Page> Opinion> Story / by Sunanda K. Datta-Ray / Saturday – June 04th, 2016