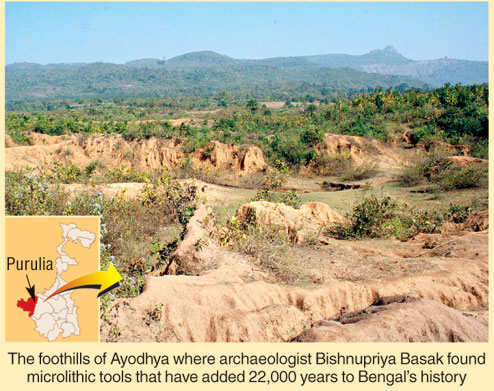

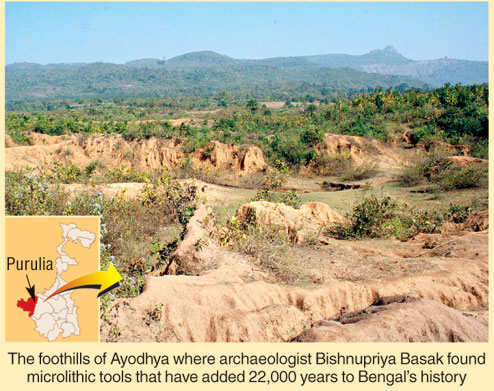

Multi-disciplinary research led by a city-based archaeologist has confirmed the presence of humans in the Ayodhya hills of Purulia about 42,000 years ago, a finding that pushes Bengal’s archaeological calendar 22,000 years back.

Bishnupriya Basak, who teaches archaeology at Calcutta University, sealed the findings after more than 12 years of intensive exploration and excavation of 25 stone-age sites she had discovered between 1998 and 2000 while working with the Centre for Archaeological Studies & Training, Eastern India.

The breakthrough came when Basak, 47, returned to the forests of the Ayodhya hills in 2011 to build on her findings using a technique called Optically Stimulated Luminescence (OSL) that establishes the antiquity of tools of a particular age.

Before Basak’s discovery, the earliest evidence of human presence in Bengal was at Sagardighi, in Murshidabad. The tools found there were dated to approximately 20,000 years ago.

“This is an extraordinary development and a breakthrough in the otherwise hazy chronology of eastern India. It marks a welcome trend in research. In this day and age, multi-disciplinary initiatives are indispensable,” said Gautam Sengupta, former director-general of the Archaeological Survey of India.

In the subcontinent, the earliest evidence of microlith-using cultures — hunter-gatherer populations that made and used the types of light stone implements found in the Ayodhya hills — is in Metakheri, Madhya Pradesh. They date back to 48,000 years ago.

Microlithic tools found at Jwalapuram, in Andhra Pradesh, are from 35,000 years ago and those discovered in Sri Lanka are from 25,000 years ago.

Basak’s discovery was reported recently in the fortnightly research journal Current Science (Vol. 107, No. 11687).

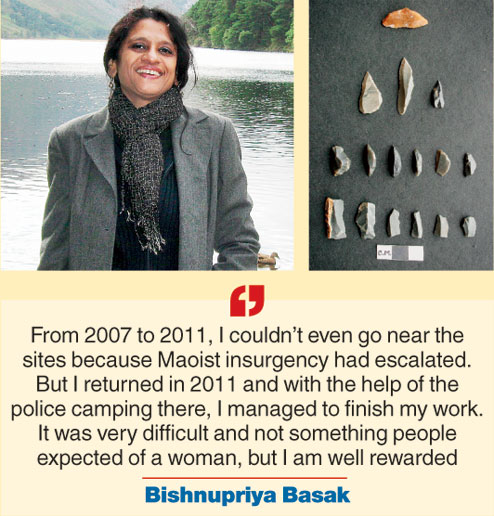

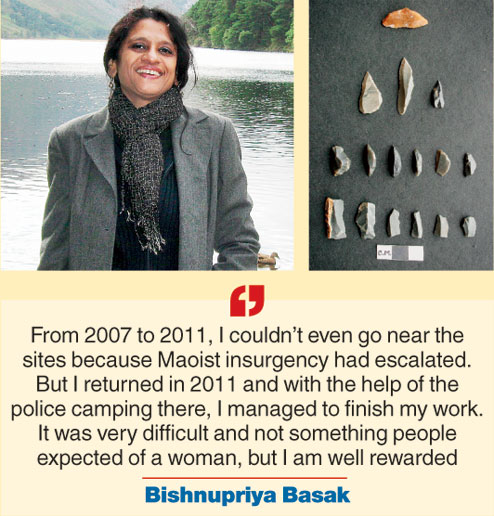

The 47-year-old had conducted part of her research under police protection in the midst of Maoist insurgency in the region, her bold quest yielding 4,000-odd microlithic tools from excavation sites at Mahadebbera and Kana alone. Mahadebbera is located 500 metres northwest of Ghatbera village, in the catchment area of the Kumari river. Kana is around the same distance northwest of Ghatbera.

“From 2007 to 2011, I couldn’t even go near the sites because Maoist insurgency had escalated. But I returned in 2011 and with the help of the police camping there, I managed to finish my work. It was very difficult and not something people expected of a woman, but I am well rewarded,” Basak told Metro.

The experts who collaborated with Basak include S.N. Rajguru, a veteran geo-archaeologist who formerly taught at Pune’s Deccan College, Pradeep Srivastava and Anil Kumar from the Wadia Institute of Himalayan Geology, Dehradun, and Sujit Dasgupta, formerly of the Geological Survey of India.

Current Science states that the microlithic tools excavated from the colluvium-covered pediment surface in Kana are from “42,000 (plus or minus 4,000) years before the present” and “between 34,000 (plus or minus 3,000) and 25,000 years before the present in Mahadebbera”.

In the subcontinent, most microlithic sites are reported from alluvial context, sand dunes or rock shelters. There are very few late Pleistocene colluvial sites. Colluvium is the material that accumulates at the foot of the hill ranges — a mix of sediment, gravel and pebbles, all brought down the hill slope through natural gravitational flow. When they form a stable surface, as in the Ayodhya hills, they are a good location for prehistoric populations to settle.

According to geoarchaeologists, the Ayodhya discoveries hold the key to research in several fields, from environmental studies to palaeontology.

“The OSL technique we used helps date sediment samples in which the tools occur to a time they were last exposed to the sun before burial or sealed by later deposits. Our samples were collected from 0.50-1.85 metres below the surface in specially-made steel/iron cylindrical tubes, making sure no light entered the trench during the process. In most cases, we had a plastic black sheet covering the top of the trench and the samples were usually collected early morning or around dusk,” Basak said.

Metakheri had been dated using the OSL method while the tools found in Jwalapuram required dating through a technique called AMS radiocarbon dating. Since there was no presence of carbon in the Ayodhya samples, the OSL method was the only reliable option, Basak said.

The samples had been first sent for pre-treatment and chemical analysis to the Wadia Institute of Himalayan Geology, where senior scientist Pradeep Srivastava dated them as belonging to the Late Pleistocene period, roughly in the bracket of “42,000-25,000 years before the present”. The rocks from which these tools had been made were identified by the Geological Survey of India as “chert and felsic tuff”.

At Sagardighi, a team led by the late Amal Roy had found microliths made of agate, chert, chalcedony and quartz. They were not scientifically dated, though. The antiquity of the tools was assumed to be 20,000 years ago on the basis of geological factors.

Subrata Chakraborty, professor of prehistory at Visva-Bharati, said accurate dating had long been a problem in Bengal because of inadequate infrastructure.

“There is no institutional set-up for accurate scientific dating in Bengal.”

The 4,000-odd Ayodhya microliths include blades and backed tools. Micro blades are small — maximum length up to 4cm — parallel-sided tools that are very sharp and suitable for cutting. Backed microliths are those that are further retouched and attached to bows, arrows and spears to hunt small animals and birds.

An intriguing facet of the discovery is that no trace of the raw material used in these tools was found in the near vicinity, suggesting that the early hunter-gatherers had travelled quite a distance to get their stones. Such instances are, of course, not uncommon even among living hunter-gatherers.

Geo-archaeologist Rajguru said the Ayodhya discoveries had opened a whole new chapter in Bengal’s history.

“We can, for instance, assert that Bengal was very much a part of the climatic changes during the last glacial period. So far it had been assumed that Bengal was always humid with plenty of rainfall. Now we have evidence that the whole of the Rahr region also experienced the dry climate that was caused by the period’s peak in glaciation. We also know that the sea level must have been lower by about 100 metres.”

Rajguru, who has been a mentor to Basak, added: “Let this instance of sustained perseverance in the face of all odds and collaboration of skills and expertise across boundaries be an example and encourage many others to follow suit.”

What message do you have for Bishnupriya Basak? Tell ttmetro@abpmail.com

source: http://www.telegraphindia.com / The Telegraph, Calcutta / Front Page> Calcutta> Story / by Sebanti Sarkar / Tuesday – October 21st, 2014