This retired professor in West Bengal is the reason many children of his region have an education and career

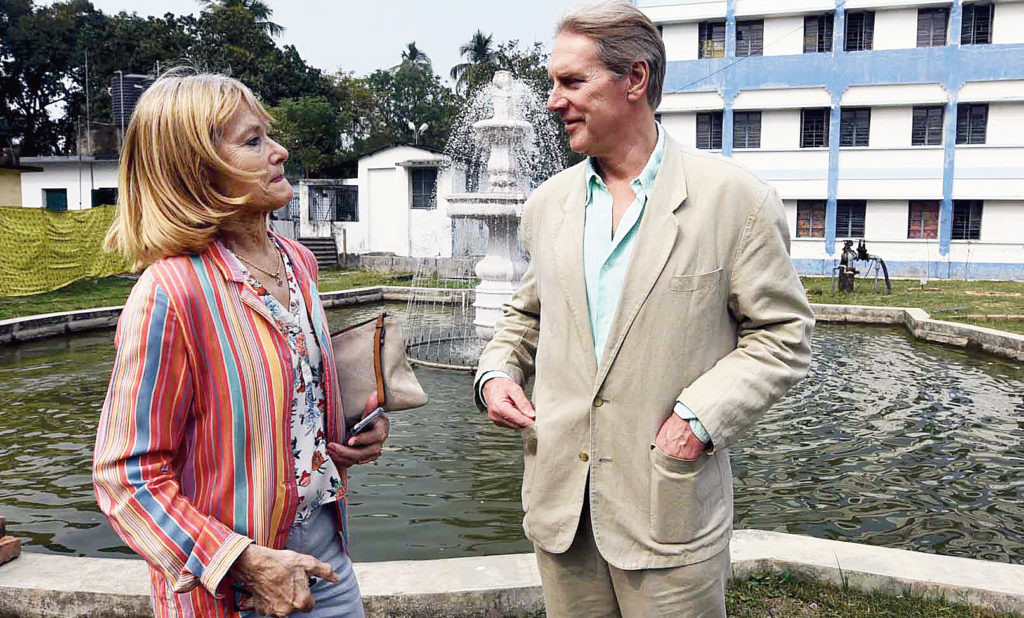

Lifeline: Professor Dilip Roy with Belaboti (left) and Uma / Image: Rabindranath Bera

Where is Dadu? Why haven’t you brought him along,” demands the petulant eight-year-old with closely cropped hair and a beige jacket over a pink frock. Her name is Bela, short for Belaboti, often referred to as Belu too. Just now she is standing akimbo, blocking the entrance to our lodgings adjacent to a two-storey mud house in Naradari, a village in Nandakumar block of East Midnapore district, five kilometres from Tamluk. The object of her query, or Dadu, meaning grandfather, is Dilip Roy, a retired professor of History and man of the house.

Bela knows that the septuagenarian had accompanied this gaggle of strangers from Calcutta to the flower show — an annual affair organised by the Tamluk Flower Lovers’ Association, founded by the good professor over 40 years ago. She is the youngest member of the Roy household, which includes Biswaranjan Pal or Bisha, Bishnupada Maity or Dipu and Joyinandan Maity or Joyi. While Bisha and Dipu are preparing for their higher secondary exams this year, Joyi is in the first year of college. There is Uma, too, whom Roy calls Kochi. She got married to Rabindranath Bera or Robi two years ago and is currently in Naradari with their newborn.

Roy is actually no kin of Bisha, Dipu, Bela, Joyi, Kochi or even Uma; at least not in the accepted sense. But each of these lives has got so entangled with his own that it is difficult to tell his story without straightening out a reference, giving an explanation or two to their lives’ stories and experiences. Also, these are lives that refract his own story, one that he himself is loath to tell.

Bisha, Dipu, Joyi were inmates of an ashram on the banks of the serene Roopnarayan river in the adjacent village, Betalbasan. When it closed down, Roy took them in. Uma is the daughter of farm labourers from Narghat village some 17 kilometres from Naradari. She had heard about Roy and his extended family from an uncle. She says, “I was not interested in studies and my parents would often beat me up for that. I literally ran away from home to escape studying and came here to work as a domestic help.”

But as it turned out, she had walked, rather run, straight into the tiger’s den. First, she was home-schooled, then at 14 she was enrolled in Class V of a local school. When the neighbours smirked, Roy — whom she and many others call Jethu, or uncle — told her, “Clear the Class X boards, that will shut them up.” Uma cleared her Class XII boards last year and is raring to resume college once her daughter is six months old.

Unlike Uma, Robi had wanted to study. He was a good student too, but his father was a hawker and couldn’t afford to support his son’s dreams. Once, while visiting his maternal grandmother in Talpukur village adjoining Tamluk, he approached Roy for help. Actually it was his grandmother who spoke to Roy as the boy explored the estate. The professor visited the boy’s school, paid for Robi’s textbooks, even arranged for free tuitions for the Class X student. And then, he supported him right through high school and graduation in every possible way. Today, Robi is team leader, back office operations, with Tata Consultancy Services, and posted in Calcutta.

Roy was born in Naradari in the late 1940s, but had left for Calcutta for his postgraduation. His father was an advocate while his mother, a housewife. When he returned home at 24, it was to teach at Moyna College, about 20 kilometres away. The youngest of three brothers, he had always been reclusive. And when he came back he chose to stay, not in the family home, but in the other two-storey mud house on the estate jointly owned by his father and uncles. He says, “The house was lying uncared for. The main house was too crowded. My parents, uncles, aunts, cousins, my Didi, her family…,” and his voice trails off as he looks at the manicured garden between the two houses.

Roy turned the ground floor into his living quarters and the upper floor he dedicated to Rabindranath Tagore. That became his library-cum-temple. He would sit there singing and listening to Tagore’s songs and reading his works. He would organise, and still does, cultural dos on Tagore’s birth and death anniversaries. “Even today, I begin my day reading sections of Tagore’s lectures, just like people read the Gita. Of course, of late, I have begun reading the Gita too,” laughs the lean, greying philanthropist.

A few years into teaching, he decided to remain a bachelor. He began to spend more and more time on his two passions — gardening and travelling. His closest friend, a doctor who died in an accident a couple of decades ago, was his travel companion. Together, they have traversed the length and breadth of the country. Somewhere along the way he began helping students from impoverished backgrounds in their pursuit of education and learning. And the more he got involved in the lives of his students, the more acutely aware he became of their hardships.

Around the beginning of the 1980s, he started providing food and lodging too to poor and meritorious young men. Today, so many years later, Roy cannot remember the first time he brought a student home. I point out that it is most odd, this date slip, of someone who teaches History, but he is distracted by Bela, who has given lunch a miss and is sulking. “She is angry with me for having my lunch without her,” he explains.

What happened was that one by one many students came to live with him. Not everyone stayed the course though. Many were taken away by their parents or guardians. But there were exceptions like Bela — the little girl from a cobbler’s family in Uttar Pradesh’s Saharanpur. She and her older sister were brought to Roy by their maternal grandmother but a few years later taken away by their parents. Her sister notwithstanding her pleas to return to Naradari was married off, but her parents eventually let Bela go back to Roy. She is being home-schooled currently.

When his college teacher’s salary could no longer sustain the expenses, Roy started to scout around for financial help. Over time he has developed a network of connections — civil servants, engineers, doctors, authors, teachers, businessmen, artists. Some pay the fee for these students, some buy the books. And while he is dogged in his pursuit of funds, Roy is careless about his own money.

To date, Naradari and its surrounding villages have produced six doctors, all of whom have flourished under Roy’s munificent shade. He paid for their admissions, entrance tests and connected them with foundations that bore their expenses at the medical colleges. And despite Roy’s advancing years, the effort to help students continues. Says Uma, “At the beginning of the new school session villagers line up for help. Every year, Jethu buys textbooks worth Rs 25,000-30,000 himself.”

During his student days in Calcutta, Roy would spend time at the city libraries. The National Library was his home on holidays. He says, “I’d go to there, borrow a book and spend hours on the veranda. I’d hardly read though. Most of the time I would look at the lawns and trees on campus.” And that’s how another interest took shoot. Roy started frequenting the neighbouring horticultural society.

His time at the horticultural society made him aware of environmental issues. In time, he launched a movement to educate villagers and schoolchildren on the need to plant trees, especially flowering ones. The movement gradually spread to neighbouring villages. Today, there are legions of gardeners working under Roy’s supervision, planting, landscaping. “Even the nurseries here seek his advice,” says Robi, the pride in his voice pronounced.

source: http://www.telegraphindia.com / The Telegraph – online edition / Home> People / by Swachchhasila Basu / February 17th, 2019