A 200-year-old palace in Odisha has a Bengal connection — a little-known love story

For most tourists, Baripada is nothing more than a gateway to the Simlipal National Park, famous for its tigers and elephants, in Odisha. That there could be tucked deep within the small town an iridescent palace with an untold love story at its core, is not common knowledge.

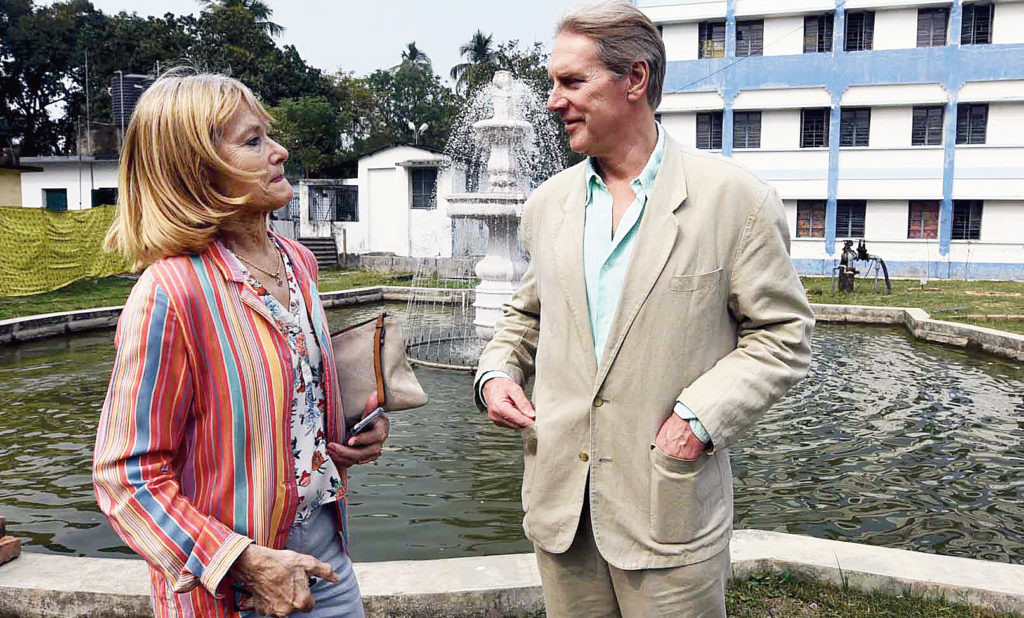

Belgadia Palace is now home to the descendants of the erstwhile kings of Mayurbhanj, the Bhanj Deos. Praveen Chandra Bhanj Deo belongs to the 47th generation. He lives in a part of the palace with his wife, two daughters and his 91-year-old mother. On the initiative of his daughters, Mrinalika and Akshita, most of this 215-year-old palace is now open for pubic viewing. Says Akshita, “We want to make people aware of the legacy of our ancestors in the district as well as in the state of Odisha.”

Before throwing open the palace doors, the sisters undertook a thorough recce of the place that revealed a gem too many. One such was the tumultuous love story of their ancestor Sriram Chandra Bhanj Deo and Sucharu Devi, the third daughter of Keshub Chandra Sen, philosopher and social reformer of 19th century Bengal.

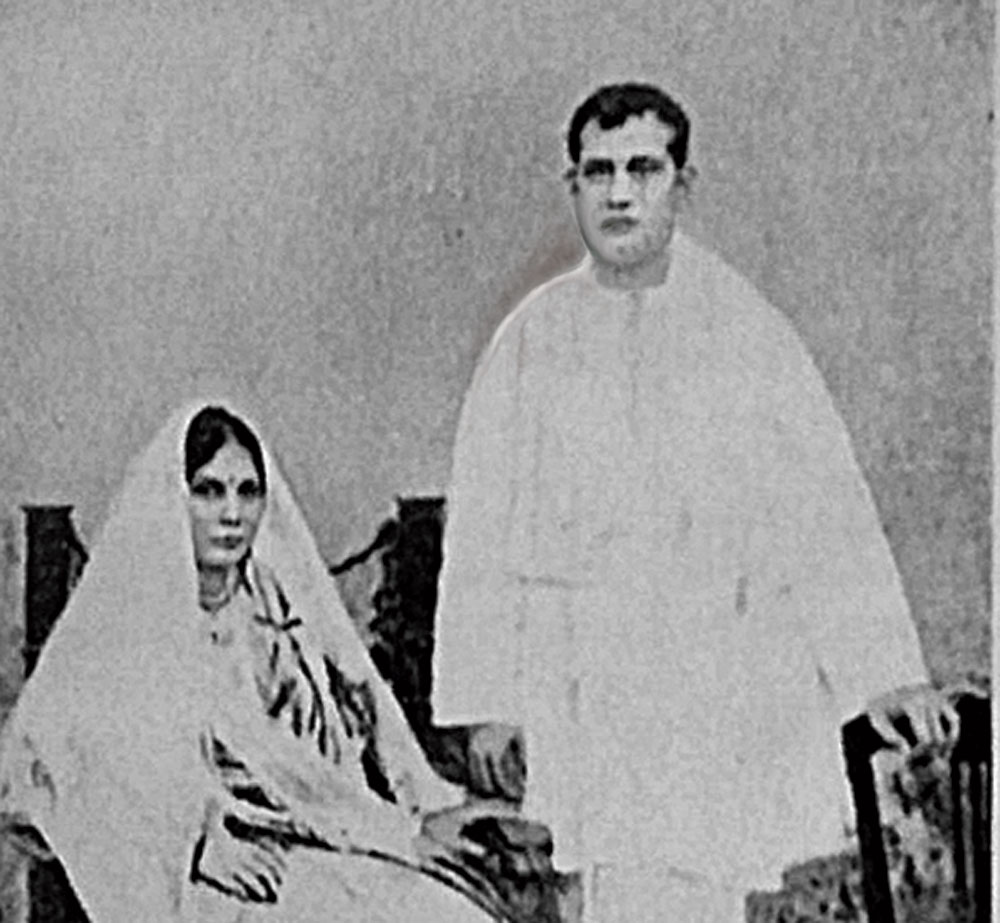

Sriram Chandra met Sucharu Devi in Darjeeling. She was educated, enlightened and a 15-year-old girl who was not in purdah. He was 18 and looking for a wife who would be his companion. After a brief courtship they got engaged.

That was in 1889. But the crown prince’s family vehemently opposed the match. “The daughter of Keshub Chunder Sen as Maharani of Mayurbhanj! The daughter of that rebel, that revolutionary! To the conservative, orthodox powers in the Hindu state this was preposterous,” reads Sucharu Devi’s biography written by her daughter, Joyoti.

The young prince was no rebel; he toed the family line and married a girl from a local royal family. But the romance between him and Sucharu Devi did not die. “We tried to persuade her to marry but nothing would induce her to forget her lover,” writes Suniti Devi, her elder sister — the erstwhile queen of Coochbehar — in her autobiography.

Sriram Chandra’s first wife, Lakshmi Devi, gave birth to two sons and a daughter and thereafter, she died of smallpox. Writes Suniti Devi, “The Maharaja’s wife died, and he came back to ask my sister to marry him. The marriage (sic) took place in Calcutta, and for some time they led the happiest lives.” This was 1904.

Since the Maharaja never dared to take Sucharu Devi to his native state, he built for her the Rajabagh Palace in Calcutta’s Mayurbhanj Road — now the building houses the J.C. Ghosh Polytechnic. They had two children — Dhrubo Narayan and Joyoti. Sriram Chandra met with an untimely and mysterious end in 1912. The accepted version is that he was accidentally shot while he was out on shikar.

Even though the construction of the palace began in 1804, it was developed in several phases. The present interiors were especially designed for Sucharu Devi since she was not welcome in the main Mayurbhanj Palace. But she visited Mayurbhanj and her palace for the first time only after her husband’s death, on invitation of her stepson, Purnachandra Bhanj Deo.

She continued to visit Mayurbhanj occasionally and was associated with social work and spiritual work in Baripada. Her involvement with the Nababidhan Brahma-Mandir in the centre of the town is known. A torch-bearer of feminism in India, she was elected president of Bengal Women’s Education League in 1931.

Sucharu Devi died in 1961 in Calcutta. To date, the rooms and verandahs of Belgadia Palace, we are told, are imbued with her refined sensibilities. As she was an accomplished painter it is believed that artists like Jamini Roy and Hemendra Nath Majumder had visited the palace.The furniture, furnishings, paintings and photographs in the palace continue to reflect her touches. Says Akshita, “She had a deep influence on most of the activities of the Maharaja, who was known as the philosopher king and also revered for his public welfare efforts.” And that is what makes intriguing the fact that to date, there is no portrait of the woman herself on display at Belgadia Palace. “This happened probably because she was never accepted wholeheartedly by the larger family and state subjects because of the difference in caste, creed and religion,” reasons Akshita. She and Mrinalika have plans to find and display the love letters and photographs of Sriram Chandra and Sucharu Devi, for all to see and appreciate.

In a letter dated January 31, 1904, the 32- year-old Sriram Chandra writes to Sucharu Devi proposing marriage once again. It goes: “Dear S… Will you then share my sacrifices if I ask you to sacrifice all worldly pleasures and to be my spiritual companion? That seems to me at present to be the voice of the Almighty. Yours S.R.C. Bhanj Deo.”

source: http://www.telegraphindia.com / The Telegraph, online edition / Home> Heritage / by Prasun Chaudhuri / June 02nd, 2019