In 1834, 36 impoverished men from Bihar and Bengal set sail for Mauritius to work as indentured labour. Over the next 80 years, more than two million people would travel to some 20 European colonies, the first of a global Indian diaspora, before indentured labour was abolished 100 years ago

When the British abolished slavery in 1834, they populated their plantations with indentured labour from India, launching the biggest international movement of workers after the notorious ‘middle passage’. In 80 years, more than two million Indian labourers were transported to about 20 British colonies before it was stopped in 1917 under intense pressure from Indian abolitionists. This year marks the centenary of the abolition of indentured labour.

Kalachand was on the verge of collapse when Champa, a fellow tribesman from the hills of Hazaribagh, came looking for him that fateful September evening in 1834. Champa too looked starved, but his eyes held a glint of excitement.

“Where have you been? I’ve been looking for you since noon. Didn’t I tell you god is great? We are going to escape this wretched life,” he said.

Kalachand didn’t say a word in response. All he wanted was to eat something. He hadn’t had a proper meal for three days now.

Champa too, and many others, had not eaten the past few days, but he suddenly seemed to have found some energy. Standing on the slushy banks of the Hooghly, he pointed to the Kidderpore depot and said, “This will save us.”

All Kalachand could see was a long shed and some small sail-ships at a distance. “Are we going somewhere,” he asked. “Tapu,” said Champa.

“Come, let’s eat something, I am starving,” he said. “Money?” Kalachand asked. “Don’t worry, I have some,” he said. He didn’t tell Kalachand it was the same Ghulam Ali, who had promised road work in Calcutta for ₹5 a month, who was now promising a brighter future.

Back in his shanty in Howrah, Kalachand found Bachu, Chuniram, Budhu, Bhola, Chota Bandhu and other friends from Bihar, Burdwan and Bankura, preparing to leave. Champa had sold them the hope of a better life on a faraway island working in British-owned sugarcane plantations. They would have legal contracts, medical help, and plenty of money to save for the future. In five years, they could come back and start a new life.

New lives, new names

The next day, September 10, Kalachand and 35 others put their thumbprints on a paper for a contract with George Charles Arbuthnot of Hunter Arbuthnot & Company. It was read out to them by a magistrate at the Calcutta police headquarters. On the contract, their names were written in English exactly the way the white men pronounced them.

Kalachand became Callachand, Champa became Champah, Bachu became Bachoo, Chuniram became Chooneeram, and Chota Bandhu became Chota Bundhoo. Most of their names had “ee”, “oo” and “ah”. It would be repeated a few million times in the next 100 years, changing Indian names to strange-sounding new variations.

After a medical examination and a five-day wait in a barrack in Bhowanipore, the men were finally herded onto a boat on the Hooghly that took them to a medium-sized sail-ship called Atlas. They were led to the lower deck while the dock workers loaded a big cargo of rice. In a few hours, the ship was heading towards the Indian Ocean. Its destination: Mauritius, the once uninhabited island off the southeast coast of Africa, discovered by the Portuguese in the 14th century and colonised by the Dutch, the French, and finally the British.

The tiny land of forests and hills, originally occupied only by dodos, rats and locusts, now had a flourishing plantocracy that desperately needed cheap labour. The abolition of slavery that year was threatening the survival of the sugarcane plantations. The planters needed workers by the thousands or faced bankruptcy. The only source of cheap labour they could think of was India, poor, overpopulated, and with millions from oppressed castes.

For the 36 men cooped up in the Atlas, it was a desperate, uncertain voyage to escape poverty and oppression. What they didn’t realise was that they were making history by launching the biggest movement of labourers in the world after the ‘middle passage’, laying the foundation for a global Indian diaspora.

50 days later

Over the next eight decades, more than two million Indians would travel to about 20 European colonies. A large number would die in transit, many would return to India, but the majority would remain, building vibrant Indian communities and sometimes even changing forever the demographies and socio-cultural and political histories of the colonies.

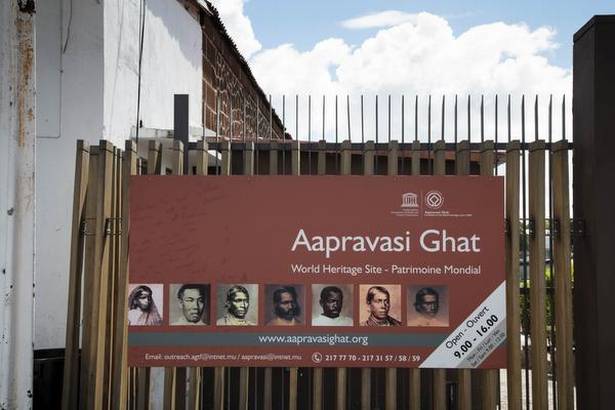

After 48 arduous days at sea and two days aboard the ship just off the shore, Kalachand and the other men set foot in Port Louis and walked up 16 stone steps carved at the harbour before they were processed and sent to the sugarcane estates. In the following years, till the turn of the next century, about half a million more Indians would climb up this flight.

Those steps, like those at Ellis Island near Manhattan that millions of immigrants to America passed through, would go on to become an iconic symbol of the history of Mauritius, and the incredible story of indentured Indian labourers across the world.

Kalachand and the others were the uninformed first participants of a ‘Great Experiment’ that the British had come up with to substitute slave labour and safeguard their commercial interests. If slaves had been hunted down and sold to the British and other Europeans, the new scheme used a method called indenture, which in simple terms meant a written contract signed by a person to work for another person or company for a fixed tenure and sum of money.

Compared to “slave” labour, indenture was projected as “free” labour, even though the workers were bonded by contract for five years under harsh conditions. ‘Double-cut’, for instance, would dock two days’ pay for a day’s absence from work.

The workers could not easily move outside their estates. If caught without their ‘immigration ticket’, they were jailed for ‘vagrancy’. The colonisers wanted to appear morally right without losing profits, but what they had surreptitiously laid out was “a new system of slavery”, as Hugh Tinker would call it in his seminal book in 1974. (A New System of Slavery, Hugh Tinker, Oxford University Press, 1974)

They chose to stay

Although their contracts promised the workers a return passage to India after five years, a majority of them chose to stay back by obtaining a new indenture. Some did return to India, mostly empty-handed, but many went back with wives and children.

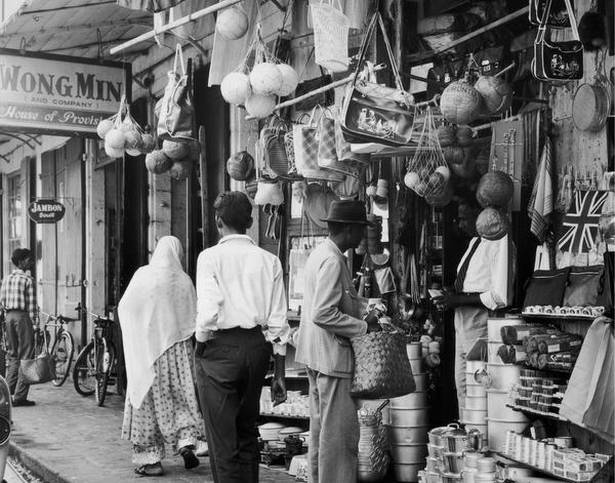

Following the Mauritian experiment, which in the next four years saw more than 24,000 Indians arriving in Port Louis (an average 500 people per month), ships carrying Indian ‘coolies’ from the ports of Calcutta, Madras and Bombay became a common maritime activity for the British.

Between 1838 and 1920, another half a million would go to the Caribbean islands and the Dutch-controlled Suriname (based on a convention on emigration signed between the governments of Netherlands and England in 1870.) By the turn of the 20th century, almost all the British colonies, from Sri Lanka to St. Kitts, had tens of thousands of Indian indentured labourers. A few thousand Indian men had been transported as slaves, lascars, artisans and labourers by European colonies during the slave-trade era, even before the ‘Great Experiment’. However, what makes the 1834 Atlas voyage historic and pioneering is that it was the first-ever lawful movement of indentured labourers in the world.

Although Kalachand and his 35 companions survived, many who arrived in subsequent trips, which had more people packed into small ships, didn’t. Infectious diseases, unsuitable food, and the stress of the journey killed them. Mortality often touched double figures.

But in the later years, with the introduction of faster ships, the mortality rates decreased even as the numbers of workers rose rapidly.

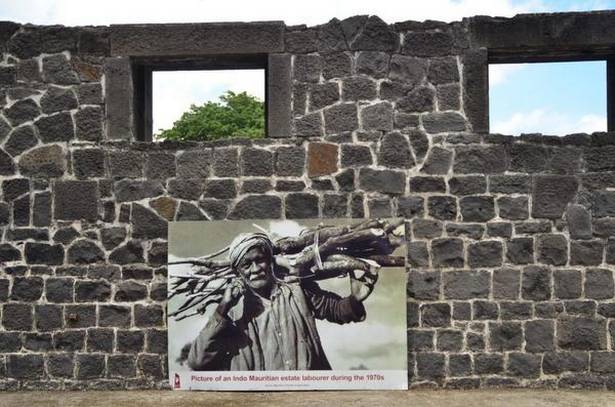

The early recruits endured slave-like working and living conditions, and many perished. The Mauritius Truth and Justice Commission in its 2011 report said: “The treatment meted out to the flow of Indian workers who came to Mauritius between 1834 and 1842 was very harsh. Their recruitment, transportation, housing and conditions of work left much to be desired. The condition of work was so appalling that the authorities decided to suspend further recruitment.”

Most of the early ones were tribal people (collectively called Dhangars) and from lower castes — they were the desperate ones who could be easily duped or even kidnapped. The same report shows the attitude of the planters towards the Dhangars: “They have no religion, no education, and, in their present state, no wants, beyond eating, drinking and sleeping; and to procure which, they are willing to labour.”

Tracing their footprints

Did Kalachand or any of the men who came with him die young? Probably yes, but they left no traceable footprints, melting into the sugarcane fields that seemed to have filled the entire island. With no women partners, they probably didn’t even leave any descendants. But some of the early ones did survive and lived long lives. Some, such as Harran, a Bihari from Calcutta, left a record of their life, including photographs, purely by chance. (Angaje, Volume 1, Aapravasi Ghat Trust Fund, 2012.)

Harran reached Mauritius in December 1836, and did multiple indentures without ever going home. He rose through the ranks, finally becoming an overseer. He was booked for ‘vagrancy’ twice and was photographed by the Immigration Depot for the first time aged 76. His photo, available in the Indian Immigration Archives of Mahatma Gandhi Institute in Mauritius, shows a nattily dressed labour-hardened man with a white beard who looks to have done well for himself.

The stories of Harran and some others, available in the archives, throw light on the early migrants who survived the neo-slavery. The details of the later migrants, particularly those who came in the late 19th century, are well documented.

In the Caribbean islands, migrants fared better because they started travelling late. Munshi Rahman Khan, who became a sort of legend in Indian indenture history for his unique autobiography, was one such. (Autobiography of An Indian Indentured Labourer, Shipra Publications, India, 2005.) Hailing from a village in Hamirpur in the United Provinces, he was a schoolteacher. On a visit to watch the Ramlila in Kanpur, he was lured by the “sugary talk” of two agents into a job in Suriname as a sardar or supervisor at a salary of 12 annas or ₹24 a month, unheard of in India at the time.

He left Calcutta in 1898, finished his five-year indenture, but chose to stay on as an agriculturist while also working as a sardar in railroad construction. He got married and bought a plot near the capital of Paramaribo. By the time he migrated, the reforms in indenture laws and land ownership and the falling sugar prices gave him a different life experience. His memoir is a rich source of history.

Workers to owners

In 1870, the planters were forced by falling prices and labour shortage into land parcelling or grand morcellement — selling small plots on the fringes of their estates to labourers. Many labourers thus became small planters. By the 20th century, there were 40,000 Indian planters who accounted for about 30% of the estates. Their descendants went on to become prime ministers and presidents, ministers, writers, academicians, artists, and businessmen. Nearly 70% of Mauritians are of Indian origin, and they dominate the island’s politics. In Trinidad, Guyana and Suriname, Indians constitute 40%, 51% and 35%, respectively, of the population.

Where are the women?

Indenture history and literature is dominated by the stories of men. But the Mauritius Immigration Office records (1853) [New System of Slavery, Hug Tinker, p-70] show that a handful of women too travelled in the early years like Deeti in Amitav Ghosh’s Sea of Poppies. The very first woman immigrant to Mauritius, and possibly in indenture history, to be issued a number by the Mauritius immigration authorities was Rimoney from North Bihar in 1845. (Satyendra Peerthum, Le Mauricien, 3 November 2016) And what a story it is!

Rimoney, 30, was a widow with a 12-year-old son when she was recruited by an agent in Calcutta where she was struggling to make ends meet. She was literate and so got a job as shopkeeper in an estate while her son was enrolled as labourer. She worked for several years, and with her savings, bought some land to become a vegetable farmer who employed other immigrants and later expanded the business.

There were other women too who migrated under extraordinary situations despite the prevailing patriarchy in India. Gauitra Bahadur, an American journalist of Indian origin, explored the 1903 journey of her great-grandmother Sujaria from Majhi district in Bihar to Guiana, in the book Coolie Woman. Sujaria’s story is fascinating because she was single, pregnant and, above all, a Brahmin for whom crossing the seas was taboo.

By 1910, about 23% of the indentured Indians in Mauritius were women — sifting sugar, stirring the juice, maintaining the mills.

An imagined India

The most remarkable feature of the indenture phenomenon is the creation of a “coolie diaspora” more than a century before the present diaspora India prides itself on. Recruited mostly from the Bengal and Madras presidencies, and to some extent from the Bombay presidency, the labourers and their descendants preserved their culture and heritage in its original form and created an India of their imagination, from handed-down memories and later, from satellite TV and cinema. A poor Tamil woman selling flowers on a Durban street dreams of meeting Rajinikanth in his Chennai home. Women, including young urban girls, who’ve never seen India, wear salwar-kameez and bindis and perform Bharatanatyam.

Temples are prominent in the diaspora’s cultural heritage, whether in Mauritius, South Africa, Fiji or the Caribbean, and Shiva and Kali temples, and Amman, Subramanya and Venkateshwara temples dominate. Shivratri, Diwali, Thaipoosam and Kavadi are gala events, with some rituals likely to surprise even Indians for their adherence to detail.

In Mauritius, for instance, a huge crater-lake atop a secluded mountain has been made into their Ganga Talo, where they celebrate Shivratri with bells and incense and rituals, an astonishing recreation of a heritage that travelled with them when they left their homeland more than 100 years ago.

The 16 steps the emigrants climbed are now immortalised as the centrepiece of a Unesco World Heritage site called Aapravasi Ghat. The Ghat, the barracks and the immigration depot have been restored and converted into a living museum. In its cool interiors, exhibits and faces tell the story of the odyssey of generations of bonded labourers from a country more than 3,000 miles away, how they built a nation with their sweat and blood, and finally, how they owned it.

As Kalachand stood at the steps, Champa probably whispered to him that the tapu they had reached was Marich tapu, Mauritius, the centre of a new India they would soon build.

@pramodsarang is a journalist-turned-UN official-turned-online columnist who lives a semi-hermit life in Travancore and adores Sanjay Subrahmanyan.

source: http://www.thehindu.com / The Hindu / Home> Society / by G. Pramod Kumar / October 28th, 2017