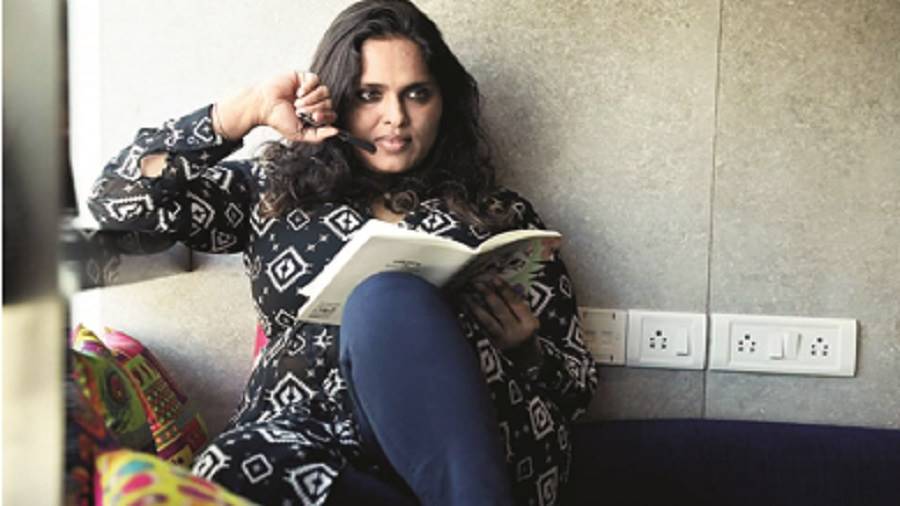

A 34-year-old Beleghata resident’s journey as a percussionist, a field still intrinsically attributed to males

Women are still a rare sight in a few places. One such spot is the one behind the tabla.

Women vocalists have earned their place on the classical music stage. But not so much as percussionists. Something about beating a surface with force strong enough to produce a sound, perhaps, is still considered an intrinsically male activity. (In older times, the beating of drums announced war, certainly a predominantly male activity.)

Rimpa Siva, however, began to play the tabla when she was about four. “I just took to it,” she says.

Now 34, the Beleghata resident is a star. She has performed in many places in India and abroad, solo, or with the biggest names in Indian classical music, and has received many awards. Numerous videos of her performances and interviews pop up on the Net, as do write-ups and at least two short films on her, one made by a French crew.

If she is still described as a leading “woman tabla player”, and if this description sounds discriminatory, even anachronistic, Rimpa brushes it aside.

To her the reference to her as a woman performer means quite the opposite. “I think it is an acknowledgment of the fact women are becoming visible as tabla players,” says Rimpa. She believes in this. But one suspects that how she is described does not really matter to her.

Very early, she surrendered her life to the tabla.

She grew up to the sound of music at her home, the top floor of the three-storey Beleghata house that belongs to her family, where she has been confined for the six months of the lockdown. Her father, Swapan Siva, a tabla player also well-known in the city as a tabla teacher. Their surname, unusual for a Bengali family, comes from the fact that a Shivalinga had been dug up on their property in Kumilla, in former East Bengal, where the family originally comes from.

Swapan was a student of Keramatullah Khan, the doyen of the Farrukhabad gharana, who lived in Ripon Street. At the beginning Swapan had thought he would encourage his daughter towards singing.

But Rimpa’s obvious talent on the tabla decided things easily. She was stunning from the start. Swapan took over her training and she became his most distinguished pupil. “My father has been my guru,” says Rimpa. She has a broad smile that lights up her face.

Her journey began early. “I performed at the Salt Lake Music Festival held at Rabindra Sadan when I was around eight. When I was about 12, I went on the ITC tour of Mumbai, Delhi and Jaipur,” says Rimpa.

Spotted by the best musicians in the country, including tabla maestro Zakir Hussain, she would soon embark on a life that would be a mad flurry of performances, travel and awards, not something every child experiences.

The French film, made in 1999, and called ‘Rimpa Siva: Princess of Tabla’, was made when she was 13. The film shows her as a student of Beleghata Deshabandhu Giris’ High School. She goes through school as if in a haze; her fingers drum on the desktop as the class is in progress. School education took a backseat. “But my school was very supportive. It postponed the selections before the class X board examination for me.” In 1997, she had toured US and Europe.

In 2004, she accompanied Pandit Hariprasad Chaurasia as the main tabla player on his US tour. In 2006, she accompanied Pandit Jasraj on another US tour. She won the President’s Award in 2007 and the Sangeet Natak Akademi award in 2017. The years in between are crowded with performances and cities, which can run into pages.

“In 1997, in San Francisco, Ali Akbar Khan himself attended my performance at the Ali Akbar College of Music. He blessed me and said that I should keep a lemon and chilli in my pocket to ward off evil,” says Rimpa. She seems quite unfazed by her achievements, but also exudes a quiet confidence. She also holds an M.A. degree from Rabindra Bharati University in Instrumental Music.

The specialities of her gharana include kaida, rela, tukra and gat, words that have entered the Bengali language from music to indicate style or attitude. She practises for three to four hours every day. Her solo performances can last up to two hours.

The lockdown makes her feel claustrophobic. It has practically stopped performance art. “I haven’t performed in six months,” she says. “Of late, I would be even travelling every month within the country, and sometimes two times abroad in a year.”

But nothing really comes between Rimpa and her music. “I live for the tabla. Everything in my life happens around the tabla. It does not matter where I am performing, with whom. When I am playing, I transcend everything,” she says.

“At that moment, I only feel peace and joy. Those who feel music know that peace and joy.”

On stage, she appears to go into a trance, lost in the music. She also looks dressed like a typical male tabla player, in a high-collar kurta, and together with her hair, she almost suggests Zakir Hussain. That is a coincidence, she says. “I can’t play the tabla in a woman’s clothes. They are not comfortable.”

She adds that she always had short hair and never cared for anything “girlie”. She did not time for friendship either.

Rimpa is also not sure about the role marriage can play in a woman’s life if she is a musician.

She feels that a lot of young Indians are showing interest in classical music now. She mentions Aban Mistry and Anuradha Pal as her illustrious predecessors in tabla, as women, and also does not shy away from suggesting that she is a role model for girls who want to take up the tabla, whether they will still be called “woman musicians” or not.

She seems to say gender is not an impediment, but you have to strike out on your own.

“Remember, girls can play the tabla,” she says.

source: http://www.telegraphindia.com / The Telegraph, Online / Home> West Bengal> Calcutta / by Chandrima Bhattacharya / September 28th, 2020